| CATEGORII DOCUMENTE |

| Bulgara | Ceha slovaca | Croata | Engleza | Estona | Finlandeza | Franceza |

| Germana | Italiana | Letona | Lituaniana | Maghiara | Olandeza | Poloneza |

| Sarba | Slovena | Spaniola | Suedeza | Turca | Ucraineana |

Greek Art and Architecture

Greek Art and Architecture, the art and architecture of Greece and the Greek colonies dating from about 1100 bc to the 1st century bc. They have their roots in Aegean civilization, but their unique qualities have made them among the strongest influences on subsequent Western art and architecture.

Greek art is characterized by the representation of living beings. It is concerned both with formal proportion and with the dynamics of action and emotion. Its primary subject matter is the human figure, which may represent either gods or mortals; monsters, animals, and plants are secondary. The chief themes of Greek art are taken from myth, literature, and daily life.

Few examples of Greek architecture or large sculpture have survived in their original, undamaged form and no large Greek paintings are known. An abundance of pottery vases, coins, jewellery, and gems have survived, however; along with Etruscan tomb paintings, these give some indication of the characteristics of Greek art. These treasures are supplemented by accounts given in literary sources. Such travellers as the Roman author Pliny the Elder and the Greek historian and geographer Pausanias saw many works that have since perished, and their writings give much information about the artists and their works.

Up until about 320 bc, the primary function of architecture, painting, and large sculpture was a public one, being concerned with religious objects and the commemoration of important secular events, such as athletic victories. The major arts were used by private individuals only to decorate tombs. The decorative arts, however, were applied chiefly to objects for private use. The average household contained a number of well-made painted terracotta vases, and some wealthier households had bronze vessels and mirrors. Many terracotta and bronze utensils incorporated small figures and reliefs.

Greek architects usually worked in marble or limestone, using wood and tile for roofs. Sculptors carved marble and limestone, modelled clay, and cast works in bronze. Large votive statues were made of plates of hammered bronze or consisted of wooden cores sheathed in gold and ivory. Heads and outstretched arms were sometimes made separately and then attached to the torso. Stone and clay sculpture was brightly painted, entirely or partly. Greek painters used water-based colours to paint large murals or decorate vases. Potters formed vases freehand on the potter's wheel; when the vase was dry, it was polished, painted, and fired.

Greek art and architecture are customarily divided into periods reflecting changes in style. Chronological divisions in this article are as follows: (1) Geometric and Orientalizing periods (c. 1100-650 bc); (2) Archaic period (c. 660-475 bc); (3) Classical period (c. 475-323 bc); (4) Hellenistic period (c. 323-31 bc).

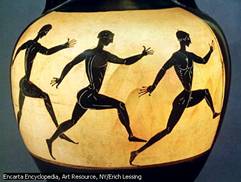

Games, Ancient, athletic contests and other types of public spectacle that were a feature of the religious and social life of ancient Greece and Rome. In Greece the games originally formed part of various religious observances. Some were held in honour of the gods, others as offerings of thanksgiving. Later on, they were held in honour of living people. The Greek games, with their attendant processions, feasts, and music, played an important role in developing the appreciation of physical beauty that is typical of Greek art and literature. Until a relatively late stage in Greek history, the participants in the games were drawn from among the citizens rather than from among professional athletes. As the games took on an increasingly professional character, their popularity declined. The four major cycles of games were the Olympian Games, the Pythian Games, the Isthmian Games, and the Nemean Games.

The Roman games, like those of the Greeks, were partly religious in nature. To ensure the continued favour of the gods, the consuls of Rome were required at the beginning of each calendar year to hold games dedicated to the gods. Funds for these spectacles were at first supplied by the public treasury. Later, corrupt politicians used the games to win the favour of the populace and vied with one another in the extravagance of the games, which eventually lost their original religious meaning and purpose.

The Roman games differed from the Greek games in several respects. In Greece the people were often participants, whereas in Rome they were mere spectators, and only professional athletes, slaves, and prisoners usually took part. Whereas in the Greek games the principal entertainment was provided by competition between athletes, Roman games often included fights to the death between gladiators and wild beasts.

Classical Discus Thrower Ruins at Olympia

Olympian Foot Race

|

Politica de confidentialitate | Termeni si conditii de utilizare |

Vizualizari: 1696

Importanta: ![]()

Termeni si conditii de utilizare | Contact

© SCRIGROUP 2024 . All rights reserved