| CATEGORII DOCUMENTE |

| Comunicare | Marketing | Protectia muncii | Resurse umane |

Faculty of Business Administration in Foreign Languages

Cigarette Market in

- the Excise' Impact on Competition -

Chapter 1

Changes of the fiscal code. Structure of the tax and its evolution

The arrangements for the taxation of tobacco products were introduced on 1 January 1993. They are the outcome of discussions which started in 1985 with the White Paper on completing the internal market, in which the Commission proposed full harmonisation of excise duties on manufactured tobacco. However, the Council chose not to take this approach and did not consider a harmonisation of the excise duty rates throughout the European Union necessary for the proper functioning of the Internal Market.

The current Community framework for the taxation of tobacco products provides for a common structure (product definitions and means of taxation) for excise duty on tobacco products as well as minimum rate levels, above which Member States are free to set their national rates at levels they consider appropriate according to their own national circumstances.

In addition, the Community legislation provides at present for a review of the structure and rates of excise duties on tobacco every four years. The Commission is obliged to make regular reports on tobacco taxation and the next report - thought as being accompanied by a proposal at that time - was supposed to be submitted to the Council in 2006.

The 2006 report took into account all relevant factors. Although excise duty is primarily an instrument for generating revenue at national level, policy-making in this area has to take the wider objectives of the Treaty into account. Given the characteristics of manufactured tobacco products, the report will pay particular attention to health considerations, taking stock of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, recently agreed within the World Health Organisation.

The control,

holding and movement by businesses of duty-suspended manufactured tobacco are

subject to common provisions laid

down in Council Directive 92/12/EEC. In accordance with the principles of the

single market, private individuals enjoy greater freedom to purchase duty-paid

goods for their own use in the

However, most of the Member States that joined the EU on 1st of May 2004 have not reached the minimum levels of taxation and have been granted transition periods until 2010. Therefore, Member States may maintain the same quantitative limits for tobacco products brought into their territories from certain new Member States as those applied to imports from third countries.

Therefore, through the EU Adhesion Treaty Romania assumed the obligation to align the minimum tax level for cigarettes with the minimum tax level of the member states until 2010 - 57% of the most popular cigarettes' (MPPC) price, but not less than 64 Euros for 1000 cigarettes.

Through the modifications made to the Fiscal Code in April 2006 by the OU 33/2006 the government approved the tax level, planning to increase it gradually until it reaches the required level. Hence, the tax increased two times in 2006, at two month's interval. The decision implies that the tax of the cigarettes will be calculated by means of a fixed quota to which a quota computed from a percentage of the cigarettes' value is to be added.

The first increase stipulated that the tobacco tax should be of 9.10 Euros for 1000 pieces plus 30% of the maximum price of retail selling (a medium tax of 32.13 Euros for 1000 cigarettes), which produced an increase of approx. 0.8 RON in the price of a cigarette package.

Starting with the 1st of July, the tobacco tax increased to 16.28 Euros/1000 pieces plus 29% of the maximum price of retail selling. The 177 article of the Fiscal Code was as well modified: the taxes due for cigarettes that equal the sum of the specific and ad valorem taxes cannot be less than 19.92 Euros/1000 cigarettes. When the sum of the taxes is less than the provided minimum taxes, they are paid.

This has been established by changing the fiscal code through the ORDER no. 3687/2008 from 17th of December 2008 regarding the level of the minimum excise for cigarettes.

Taking into consideration the provisions of art 177 par. (1^1) from Law no. 571/2003 regarding the Fiscal Code, including the later modifications and completions, based on art. 11 par. (4) from Government Decision no. 386/2007 regarding the organization and the functioning of the Ministry of Economy and Finances, with the later modifications and completions, the Minister of Economy and Finances provides the following order:

Art. 1 - The level of the minimum excise for cigarettes in the period between the 1st of January and 30th of June 2009 inclusively is of 44.64 Euro/ 1000 cigarettes, respectively of 166.79 lei/ 1000 cigarettes.

Art. 2 - The present order is published in the Official Monitory of Romania, Part I.

Minister of Economy and Finances, Varujan Vosganian

The table illustrates the current prices for the most popular brands in each quality class, and their expected evolution, according to the new fiscal provisions adopted. It is noticeable that the prices will not increase proportionally for premium cigars and mid and low quality cigars, which will lead to a series of negative economic effects, explained later on in this case study.

|

TYPE |

PRESENT PRICE |

1st of April |

1st of September |

1st of January 2010 |

|

Premium ( |

6.5 lei |

7.2 lei |

7.5 lei |

9 lei |

|

Medium ( |

5.8 lei |

6.6 lei |

7.5 lei |

8.5 lei |

|

Cheap (More, |

5.3 lei |

6.3 lei |

7 lei |

8 lei |

Chapter 2

The analysis of cigarette market in

The Romanian tobacco market amounts over 1 billion Euros, with a total volume of 35 billion cigarettes sold, with minimal annual fluctuations, and is dominated by three large international producers, Philip Morris, British American Tobacco, and Japan Tobacco International, who dominate almost 90% of the market share. The remaining 10% is controlled by other producers or importers (a competitive cluster, because these firms have low market shares), making the market look like an asymmetrical oligopoly.

Surveys show that Romania is on the second place in Europe as number of smokers, Romanian people being considered among the most faithful fans of cigarettes at world level as well, as shown by a study Euromonitor.

According to the

retail audit data provided by ACNielsen

The most sold are the ones in the medium price category (approximately half of the market). The cheap price category owns approximately one quarter of the market, almost the same percentage as the luxury ones.

Therefore,

premium products account for 10 % of cigarettes sales in

The falling of the communist regime in 1989 facilitated the entering onto the Romanian cigarettes market of the large international cigarettes producers.

At the beginning

of the 1990s,

Nowadays, the supremacy on the market is fought for by players with international notoriety, like British American Tobacco, Philip Morris and Japan Tobacco International. The national brands, like Snagov or Carpati could not handle the competition, and have now a very low market share. At the moment the leader on the Romanian cigarettes market is British American Tobacco.

British American

Tobacco (BAT) has experience in cigarettes production of more than 100 years.

The company was formed through joint venture between The American Tobacco

Company (USA) and The Imperial Tobacco Company (GB), in 1902. In time, the

company grew, reaching 90000 employees, 81 cigarettes factories (including in

In 1990 they

decided to grow their business by focusing solely on tobacco, having the vision

to regain leadership of the global tobacco industry. Over the last decade or

so, their market share has increased by nearly 50 %. They are now the second

largest international tobacco group, accounting for some 17 % of the global

market. In

One of their advantages is that they hold a

high number of brands: their portfolio of some 300 brands is based on distinct

'must-win' consumer segments - international, premium, lights and adult smokers

aged under 30. They have four Global Drive Brands:

While constantly developing their Global Drive Brands, they are also increasing the profile of Vogues in the super premium segment and Viceroy, a leading low price international brand.

Although 95 % of

the world's smokers consume ready-made cigarettes, they also have cigar,

roll-your-own and pipe tobacco in their portfolio, including the hand made

premium

Some of the

companies from the group also sell Swedish- style snus, a form of smokeless

tobacco that is placed under the lip and is reported to be less harmful than

cigarettes, sold under the Lucky Strike, Peter Stuyvesant,

Philip Morris

international (PMI), part of the Altria group is the leading international

tobacco company, with products sold in approximately 160 countries. In 2008,

they had over 75000 employees, and 58 factories, holding an estimate 15.6 %

share of the international cigarette market outside the

Being international leaders on cigarettes market, they own more than 150 brands, out of which seven are of the top 15 brands in the world. Their top 10 brands by volume are Marlboro ( world's number one cigarette brand), L&M, Chesterfield, Bond Street, Philip Morris, Parliament, A Mild, Lark, Morven Gold and Next.

While they focus primarily on cigarettes, their business development interests extend to other tobacco product categories.

The third major competitor internationally, and also in Romania, is Japan Tobacco International, with a global market share of 11 %, selling 385 billion cigarettes in 2007, and employing 23000 people in 40 offices and 30 factories around the world.

JTI was formed

in 1999 when JT purchased the international tobacco operations of

Among other brands, produce three of the top five worldwide cigarettes brands: Winston - the fastest growing brand worldwide, Camel and Mild Seven - the global leader charcoal filter cigarette. Their portfolio also includes Benson & Hedge and Silk Cut - two leading Virginia brands, the prestigious Sobranie of London, Glamour - the fastest growing super slim cigarette brand, and their international value brand, LD.

They also have a portfolio of brands that they market regionally to complement their Global Flagship Brands.

JTI is also a significant player in the OTP (Other Tobacco Products) arena, with Hamlet cigars, Old Holborn, Amber Leaf 'roll-your-own' tobacco, and Gustavus Snus (Swedish style smokeless tobacco).

SNTR (Societatea

Nationala "Tutunul Romanesc") is the fourth cigarettes producer and marketer in

Chapter 3

Economic Implications of the cigarette tax: producers, consumers, state

A reduction in tobacco consumption has been targeted as a major public health policy by the European Union. Since 1987, there have been several directives and other legal texts concerning this issue. Despite this, the consumption of tobacco, mainly cigarettes, remains unchanged or continues its upward trend (depending on the country studied) and public goals are not being met.

To achieve these goals, the many available policies need to be harmonized within each member state as well as within the EU.

The standing policies in the EU can be classed into four categories: informative/educational, fiscal, prohibitive, and incentive.

In our case, we discuss the fiscal policies and their economic implications regarding consumers, but also producers and the state.

Although taxation is considered an appropriate instrument to combat tobacco consumption, traditionally it has not been explicitly linked to public health. It is commonly accepted that tobacco consumption is reduced when the products are heavily taxed. Higher prices dissuade consumers, especially young people because of their lower disposable income. Still, the tax increase has many other implications, and unfortunately the most significant ones have nothing to do with public health.

The effects of a tax must be analysed taking into account more different aspects: those to whom these taxes are imposed are not always the ones that actually pay them and the demand and offer elasticity for the product in question influences the effect of applying the tax. When taxes are increasing and the demand decreases, the most affected are the small firms- with small market shares, small profits and which produce goods with lower prices.

The tax increase has a significant impact on the entire industry, but if you look carefully at the structure of the tax, you might notice that the ones who are most affected are the poor quality cigarettes, whose price will get to close to the one of superior quality cigars. Therefore, the obvious consequence will be setting the premises for unfair competition on cigarettes market, by favourizing certain producers, which leads to discrimination.

Because of the regulations that set a minimum tax level and the process of taxation, the taxes applied to filter cigarettes reach approximately 65 % of their price, whereas for non-filter cigarettes they are 90-95 % of their price. This means that the price of the cheaper cigars will increase by a bigger percentage than the price for more expensive ones. The producers of low-quality cigars will be indirectly eliminated from the market, through the creation of discriminatory conditions.

This will influence in a negative way the Romanian economy, because prices will increase more in the inferior segments than in the superior ones, and most of the producers of low quality cigars segment are Romanian.

From economical point of view, what we need to observe is that the direct effect will be a market compression. Because of the structure of the taxation, the premium segment will obtain a part of the market share of the sub-medium and medium cigars producers. This will mean the elimination of these producers of sub-medium and medium cigarettes, and, at the same time, it will lead to consolidating the market position of premium and prestige cigars producers, who will share the remaining market shares. This way, the transformation of the market from an asymmetrical oligopoly, into a symmetrical oligopoly will be favourized.

Article 4 from the Competition Law stipulates that a large enough number of producers must exist so that the price is a result of the balance between offer and demand. In our case, the computations show that the main producers on Romanian cigars market will remain BAT and PM, whose portfolio consists mainly of premium cigarettes. These two producers will be the ones distributing between them the market shares of their eliminated competitors, JTI (the main competitor), and other small competitors, producers of cheap priced cigars.

The obvious result is that there will not be enough competitors on the tobacco market, which means that the very condition of a competitive market will be eradicated, and will lead to a breach of the article from Competition Law stated above.

The type of market that will be created is only advantageous for the two main competitors, but means discrimination for the small producers, and has only disadvantages for the consumer, who cannot influence the price any longer.

By imposing the minimum tax, the small producers will be in a disadvantageous place, no matter what they choose to do. They can sell at a lower price, in order to keep their customers, but they will lose because they will still have to pay the minimum tax. Their other option is to sell at the minimum price, but that means they will lose clients, and again, they will lose because their sales will go down. These are the only options they are left with and they are equally disadvantageous, therefore affecting their autonomy. In the end, the situation is against their freedom of trade, one of the freedoms the EU principles are based on.

The consumer is also in a disadvantageous situation. Economically speaking, the welfare of the end user is assured by the quantitative, qualitative and diversified existence of the goods on the specific market, depending on their utility, as perceived by the user.

The consumers' welfare will, therefore, be seriously affected, because he will have few options to choose from, and will be forced to accept a higher price for a base or value product, price which he cannot influence.

The possibility for him to maximize his satisfaction is abolished when eliminating the diversity in types of homogenous goods, in our case cigarettes.

On the free trade economical world within the EU, it is against all policies and regulations to create a market where the competition is abolished, so the price has nothing to do with the dynamics between offer and demand, and the consumer cannot influence in any way the price or the evolution of the offer. Yes, cigarettes can be harmful. But wasn't the customer supposed to be free to choose? Wasn't the consumer supposed to be the king? Isn't that what our modern economy and society was supposed to be based on?

When analyzing the economic

effects of the tax, we must take into consideration the market's

contestability, therefore the importance of entrance barriers. The tobacco

market in

Big firms with large number of sales have a competitive advantage as compared to firms that have a low level of sales, once there is an important potential for economies based on the extensive division of labour.

Where the size of the

company gives an advantage of cost because of the existence of either scale or

scope economies, there is only room for a few companies, although the market

may be large enough. The size-based cost advantage will compel the industry to

turn into an oligopoly, except the case where the government interferes. This

is the case of cigarettes market in

In terms of tobacco

industry in

This brings us to the acknowledging installation costs especially advertising as an important entrance barrier.

The tobacco industry is the perfect example of combined used of brand notoriety and advertising acting like a market entrance barrier. Intense advertising creates an entrance barrier by increasing the installation costs for new products.

Although the taxation system was imposed by the state itself, there are strong arguments that it might end up being disadvantageous for it.

The economic theory underlines the fact that an increase of taxation rate above a certain level would rather decrease than increase the state's revenues from taxation. Basically, it is a proven fact that when obligations exceed the limits of equitable requirements, companies and individuals don't pay their debts any more as supposed to.

An erroneous choice of taxation method by the state eventually turns gains into losses. Hence, the introduction of the minimum level for excise and of the method of taxation has negative effects, because the method influences price increases on the segment, affecting strongly low income consumers. What happens is many of the low income consumers turn to cheaper products, which can only be found on the black markets. We will witness an increase of the degree of tax evasion and a decrease in state revenues from taxes. They claim that the main purpose of this tax is public health, not the money cashed by the state. But can an issue like public health be solved by aggravating another serious problem of the economy- tax evasion? Large scale smuggling, which involves the illegal transportation, distribution and sale of huge amounts of tobacco products and the avoidance of taxes already represent the highest proportion of illegal commerce.

Taking away the customers' freedom of choice, forgetting about the market economy, discriminating small producers, helping a few big companies set the trend in one of the largest global markets, encouraging tax evasion and illegal commerce, basically forgetting about all principles that got us here, is this really the EU answer? And if so, what exactly is their question?

Chapter 4

State aid elements discussion in this case

A company which receives government support obtains an advantage over its competitors. Therefore, the EC Treaty generally prohibits State aid unless it is justified by reasons of general economic development. To ensure that this prohibition is respected and exemptions are applied equally across the European Union, the European Commission is in charge of watching over the compliance of State aid with EU rules.

As a first step, it has to determine whether a company has received State aid, which is the case if the support meets the following criteria:

There has been an intervention by the State or through State resources which can take a variety of forms (e.g. grants, interest and tax relieves, guarantees, government holdings of all or part of a company, or the provision of goods and services on preferential terms, etc.);

The intervention confers an advantage to the recipient on a selective basis, for example to specific companies or sectors of the industry, or to companies located in specific regions;

Competition has been or may be distorted;

The intervention is likely to affect trade between Member States.

By contrast, general measures are not regarded as State aid because they are not selective and apply to all companies regardless of their size, location or sector. Examples include general taxation measures or employment legislation.

By analyzing

these criteria, we may see that the cigarette market in

In addition to this, the excise tax is indeed likely to affect the trade between Member States, because the Romanian producers are gradually eliminated from the market, due to the higher increase in their prices, and this way, the most viable option will be the import of cigarettes from the notorious foreign producers.

Tobacco tax

increases are encouraged. The treaty states that 'each Party should take

account of its national health objectives concerning tobacco control' in

its tobacco tax and price policies. The treaty recognizes that raising prices

through tax increases and other means 'is an effective and important means

of reducing tobacco consumption by various segments of the population, in

particular young persons.' In the Position Paper included in the

negotiations documents with European Commission for

At governmental level the most active body in this field are the Romanian Ministry of Health and also the National Agency against Drugs, who show an increased interest in the tobacco control matter.

Here are few of the provisions concerning public health, but which have no discriminatory effect on certain cigarettes producers:

. Directive 98/43/EC of the European Parliament and the Council on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States relating to the advertising and sponsorship of tobacco products (annulled in 2000), as well as

Directive 89/552/EEC which imposes a prohibition on television advertising of tobacco products

. The Law for approval of the Governmental Emergency Ordinance no. 55/1999 for banning the tobacco products advertising in cinema halls and banning selling tobacco products to minors

. Law no. 148/2000 regarding advertising, which provides: establishing of the mandatory norms for advertising, tv-shopping and sponsorship, banning smoking in closed public places, labeling the tobacco products; establishing the health warnings, involving the radio and television national companies in broadcasting anti-tobacco messages.

There are four general aims for EU policy in the sphere of tobacco taxation: to achieve tax harmonization and uniformity, to discourage the consumption of tobacco products, to raise revenues for the government, and to correct negative externalities from smoking.

Since the government is launching a full-scale attack on the tobacco industry, taxes have become the medium by which prices are controlled. There have been several studies concerning the consumption of cigarettes and the explanatory variables associated with that consumption. All of the studies have shown that taxes can be significant in reducing smoking. Recent economic analyses have convincingly demonstrated the efficacy and affordability of tobacco control measures in all countries, rich and poor alike. Tobacco control is both effective and cost-effective. World Bank refutes the widespread myth that tobacco control strategies are a Western luxury, and that poor countries cannot afford them. Moreover, elements of tobacco control, in particular raising taxes on tobacco products, constitute economically sound policies as well as a public health strategy. Taxes can serve as a self-control device for sophisticates to combat their own time-inconsistent tendencies by helping them realize their long-run preference of less smoking and increased long-run well being.

Tobacco products are so-called "normal goods" (despite the strong addictive

properties of nicotine products), with an inelastic demand. This means that if the price

increases, consumption will fall, but by a smaller percentage than the price increase. Tobacco provides substantial tax revenues to governments. This revenues excise taxes that are especially significant in low income countries whose income tax systems tend not to be well developed. Because there are usually a small number of cigarette manufacturers, it is relatively easy to levy and collect excise taxes on cigarettes. Higher tobacco taxes that raise the price of cigarettes and other tobacco products have proved to be the single most effective tobacco control measure. The price rise causes consumption to fall, but, as we have said before, by a smaller percentage than the price rise. Some smokers quit, others cut back, and would-be smokers are deterred from starting. Young people and adults with low incomes tend to be especially sensitive to prices. With higher taxes, smaller quantities of cigarettes are sold, but the tax per pack is higher, generating larger total revenues,even in countries where taxes and prices are very high.

From a theoretical viewpoint, taxes are especially important for limiting cigarette consumption by young, usually naive, potential addicts. This logic is confirmed by numerous studies indicating that cigarette taxes are especially effective in reducing consumption and in preventing addiction by younger individuals.The impact on young, is another important consideration in evaluating the impact of a cigarette tax. The health care community emphasizes that young smokers are unaware of the full risks of smoking in terms of both its health risks and its addictive nature.

Tabacco control policies, and interventions have proved to be highly cost-effective in improving health outcomes,which is an important aspect of internationally agreed development goals. Increased government revenues from higher tobacco taxes could be used in pro-poor ways, and to achieve important development goals. Large reductions in tobacco use could lower the disease burden and mortality among smokers and their families, and release disposable income for more beneficial uses

There are some arguments which prove, that the tax increases can be progressive, depending on the extent to which poor smokers reduce their consumption in response. If -as may well be the case- low income smokers cut consumption by more than the price, tax increase, then increases in tobacco taxes will reduce their overall tax burden. And given the reduction in risk and consequent health gains that will result from lower use of tobacco, tobacco tax increases may be highly beneficial for poor smokers. In any case, the distributional impact of a single tax should not be considered in isolation from that of the broader system of taxation and government spending. All or part of additional revenues from higher tobacco taxes could be used in a pro-poor way to achieve health and broader poverty-reduction goals

The World Bank Report found in 1999 that the impact of a tobacco tax would be greatest on low income households because they respond more strongly to price increases, with more poorer smokers reducing or quitting smoking. This means that overall, the increase in tobacco tax as a percentageof their income tends to be lower than it might otherwise be. Higher taxes combined with programmes to encourage poorer consumers to quit can thus achieve disproportionately significant gains for the poorest consumers, not only in providing an incentive to quit (with potential large health benefits),but also in freeing-up funds to be used for more beneficial purposes.

There are a lot of people who think, that higher taxes and prices increase smuggling While this may occur, the answer is not to back away from a tax, but to address smuggling directly. There are sevral methods that can be applied in order to decrease or to stop the smuggling: stamps on all tobacco products, with fines on those who sell products without stamps. Other strategies include warning labels in local languages, licensing of exporters and importers, and better record keeping by manufacturers.

One can criticize higher prices imposed as part of tobacco control, because they inflict substantial costs on individual smokers. This is true, most people who smoke say they want to give it up, and if smokers consider the costs high, this may assist them to quit.

"The increses on the tobacco taxes are a good thing for the health, for the budget and for the economy".

Increasing cigarette taxes is a win solution for Romanian Government - a health win that reduces smoking and saves lives; a financial win that raises revenue and reduces health care costs; and a political win that is popular with the public.

In Romania the taxes represent almost 53% from the retail price of the cigarettes. Analysts from international institute mentioned that 21% from the adults are smoking daily, and the increase of the excise represents the most powerful instrument used to reduce the smoking, death rate and all the expenses from health insurances.

The Romanian

Government stated: ''We are estimating that the progressive increase of the

tobacco tax will determine an increase in the state revenues.

The Ministery of Public Finances announced that the application of all the modification from the Fiscal code are going to bring revenues to the state budget, of 590 mil. RON, which represents 0.10 % from the GDP. The social impact is positive in the opinion of OU representatives, because the reduction of the tobacco consumption determines an increase in the population health condition, and a decrease of expenses from the budget allocated to the health department. The Minister of Finance anticipates a decrease in the level of sales for cigarettes, and states that this is a good thing for the business environment OU, because creates a competitive environment, fair for producers and as well for consumers.The raise of the cigarettes tax is going to determine an increase with 20% in the cigarettes prices, and a decrease in the consumption with 8%.

Chapter 5

Statistics on different level of cigarette taxes in different EU countries. Comparison and discussion.

Tobacco is heavily taxed in most European countries and this tax

has a great revenue generating capacity. For example in

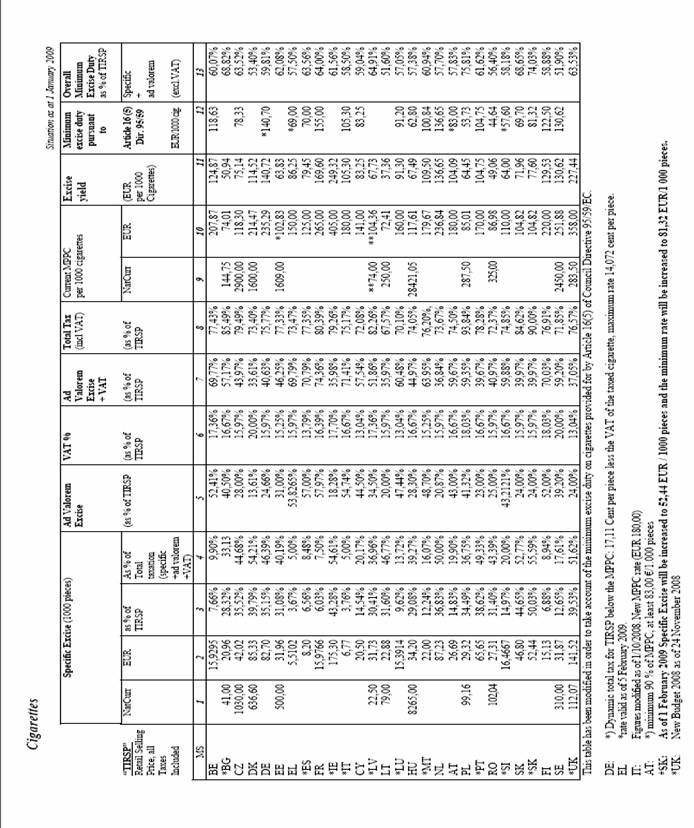

According to the latest EU council directive (2002/ 10/CE), all member states agreed to impose a cigarette excise tax consisting of a specific as well as an ad valorem component. Currently, the minimum total excise tax is 64 per thousand cigarettes ( 1.28 per packet of 20). The minimum total level of excise taxation on the most popular price category has to be 57% of the retail price, including the value added tax (VAT). Also, the specific element must be no less than 5% and no more than 55% of the total tax on the most popular price category, including VAT.

Although in most member states total tax represents,

on average, 75% of the retail price, there are substantial differences in the

absolute amounts of total taxes and retail prices of the most popular brands.

For example, for the most popular brand in

The corresponding figures in the

In northern European countries, the specific component dominates the tax structure while, in the Mediterranean countries, there is a preference for the ad valorem element. This translates into high prices in northern EU and low prices in southern EU countries.

Additionally, most of the member states that joined the EU on 1st of May 2004 have not, as yet, reached the minimum levels of taxation required of the EU and have been granted transition periods until 2010. Both circumstances raise the possibility of smuggling and bootlegging, i.e. the purchase of tobacco products in excess of cross-border allowances in low tax countries for sale in high-tax countries without paying the excess duty.

The economic and public health effects of such activities are highly negative. Also, while in northern EU countries there is no wide price range between brands, in the south it is very easy to find cheap brands and, as such, fiscal policy is not as effective in reducing consumption because smokers can switch to cheaper brands.

The establishment of the Common Market in the 1960s and its transformation into the Internal Market in the early 1990s required the creation of a special common tax system that would allow the proper functioning of four basic freedoms between the EU Member States on which the Common Market was (and still is) based, particularly the free movement of good and services.

At the very beginning, economic and social structures of Member States differed in many ways. They had dissimilar tax systems that could distort flows of goods and services. The basic differences were related to the division of the tax burden as between direct and indirect taxes, and the technical organization of taxation. The original idea of a single fiscal territory was soon abandoned as completely unrealistic, since it would require a too wide harmonization of tax systems and particular taxes in the EU. Member States were not ready for concessions, since taxes are the most significant source of revenues for their budgets. The goal of single fiscal territory was then substituted by the fiscal neutrality between Member States. Its purpose was to ensure the elimination of influence on trade flows within the Community and to establish equal conditions of competition among the Member States.(Tyc, 2008)

The common system of taxes on consumption is needed also for another reason: it should create completely impartial conditions of competition in the Common Market. Different tax rates (not only VAT, but direct taxes as well - for instance, income tax may distort the competition creating different conditions for producers in different Member States.(Moussis, 2006)

Currently, cigarettes are one of the most accessible goods in all countries. Nearly all governments tax tobacco products. However, significant differences exist across countries in levels of tobacco taxation. Some of these taxes are specific or per unit taxes; others are expressed as a percentage of wholesale or retail prices (ad valorem taxes).

Taxes account for a greater share of the retail price (two-thirds or more) in high-income countries. In low- and middle-income countries, taxes are generally much lower and account for less than half of the final price of cigarettes.(Moussis, 2006)

The last researches show that EU does not have a unique model for the structure of the excise. There are some countries where the dominant component in the excise structure is ad valorem and other countries where the specific component is dominant. These structures are influenced by the level of living of the population, the competitional structure of the market, local producers and so on. On the one hand, we can notice a certain consitency for EU member states as following: in the Mediteranean countries, less developped ( Spain, Portugal, Greece) the component ad valorem is predominant, as for in the Northern countries that are more developped the predominant component is the specific one. On the other hand, the Southern countries, with a strong tobacco tradition have mentained the stucture on the ad valorem component. (Table 2) For the Eastern countries the local producers have been incorporated by the transnational ones, therefore the structure of the excise is irelevant for the competition. Therefore the structure of the excise is relevant for those countries where the local producers are still independent, having a portofolio of products that has not change significantly. The market researchers have estimated that for rich countries, the demand will decrease by 4%, while the cigarette price will increase with 10%, which will lead to an elasticity of -0.4. In middle and low income countries, the elasticity will be between -0.6 and -1.0. As a consequence, if the demand is inelastic, the taxes will be almost entirely paid by consumers, and if the demand is prefectly elastic the taxes will be paid off by producers. (Dima, 2007)

The less elastic the demand, the less effective the tax will be in reducing cigarette consumption, but the more the gain in tax revenues. Revenue is therefore increased regardless of the rate of consumption.

Table 1 reports price indexes for several EU countries adjusted by purchasing power parities including taxes. Price indexes have been adjusted by purchasing power parities, so that if the Tobacco price index (TPI) is 130, this means that tobacco is relatively expensive compared with other consumption items.

TABLE 1: PRICE INDEXES IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

|

EU country |

Price index(%) |

EU country |

Price index(%) |

|

Austria |

Italy | ||

|

Belgium |

Luxembourg | ||

|

Denmark |

Netherlands | ||

|

France |

Portugal | ||

|

Germany |

Spain | ||

|

Greece |

Sweden |

|

|

|

Ireland |

UK |

Evidence showed that taxes seem to reduce tobacco consumption, but, unfortunately, they do not influence the decline of smoking prevalence. Smoking is an individual decision depending on a complex reasoning process. Higher taxes for cigarette might hide two separate effects, in particular, the people quitting smoking and the influence of more people entering into the market.

TABLE 2: SMOKING PREVALENCE IN EUROPEAN UNION COUNTRIES

|

EU country |

Smoking prevalence |

EU country |

Smoking prevalence |

|

France |

UK | ||

|

Belgium |

Greece | ||

|

Netherlands |

Spain | ||

|

Germany |

Portugal | ||

|

Italy |

Finland | ||

|

Luxembourg |

Sweden | ||

|

Denmark |

Austria | ||

|

Ireland |

|

||

The European Commission wants to increase and harmonize taxes on cigarettes across the European Union in a bid to cut smoking and reduce tobacco smuggling. Harmonizing the tax level in all member states will help reduce illicit trade and cross-border shopping, which undermine the revenue and the health objectives of member states which impose high taxes to deter smoking.

Cigarette prices

currently vary widely across the 27-member bloc - from an average of 0.06 cents

per cigarette (or 1.20 euros for a packet of 20) in

%Tax

= tax as percentage of total cigarette price; i.e., tax/price

%Tax

= tax as percentage of total cigarette price; i.e., tax/price

Chapter 6

Conclusions, Recommendations, Personal Opinions

This analysis of the cigarette market and specifically the excise' impact on the competition on this market is, without saying, an economical analysis, and maybe even a social one. It is important to understand that the competition regulations, taxation policies and regulations related to it, as well as any other political factors presented have nothing to do with the public health issue, which is a totally different problem.

Some might argue

that the tax now imposed is a measure for public health, but we question this

because of the structure of the tax that set the premises for a discriminatory

environment, as explained previously. Also, we must acknowledge all the

negative effects of the current fiscal policies and realize that public health

issues, although not to be ignored, cannot be answered to by damaging the

society and the economical environment of

The cigarettes' case supports the fact that the Romanian market experiences a period of accelerated fiscal transition and dynamics, and cannot, unfortunately, be considered a functional market.

The laws of market economy state that the consumer is the one who decides which producer is to stay on the market and which one has to exit. For a good functioning of the economy, the state should not attempt to do his by itself, voluntarily or involuntarily, through different sorts of measures it takes. The present structure of the excise tax and aggressive increase might end up being such a measure, and no one will benefit in the end.

Still, it is hoped

for that once the transitional period towards the goal recommended by the

European Union and assumed by

As for the reasons why this excise tax increase may bring a benefit to the population, we find that the vast majority of smokers indicate a desire to cease, but are unable to do so. While youth usually do not underestimate the adverse health impacts of cigarette smoking, they often underestimate the addictive potential for themselves. Both of these observations indicate that most smokers and especially young smokers are time-inconsistent. This is a telling argument for supporting a reasonable cigarette tax increase in our view.

Taxes can serve as a self-control device for sophisticates to combat their own time-inconsistent tendencies by helping them realize their long-run preference of less smoking and increased long-run well being.

Taxes provide naive smokers with a self-control device and help correct the misperception problem regarding their time-inconsistency behavior (Gruber and Koszegi).

An increase in the excise tax would also serve to reduce consumption by naive and potential addicts, especially among youth. Specifically, when you raise taxes, the young people who don't take up smoking are primarily those for whom the costs become a real barrier, and those are poorer, younger people. So that the net impact on poorer communities is that less people smoke, and therefore, excise taxes do not, on the whole, take more money proportionately from poorer communities than from rich communities. That is tough, however, for the person who is a smoker in a low-income community, and it is an issue that many people have wrestled with.

The increase that is current being requested is not extreme and would give Romanian cigarette excise tax a rate close to but still less than the EU's average.

Competitive markets are economically efficient if no one can be made better off without making someone else worse off (no consumer or producer can increase well being through further trade) and there is no market failure. For cigarette consumption, market failure could be due to externalities, to incorrect risk perception, or to addictive behavior (Jeanrenaud and Soguel, 1999).

As a conclusion ...... are the most persuasive in our view.

References

Stoica, Dragos, Jurnalul National, Tigarile si bautura, mai scumpe de la 1 aprilie, 20.03.2009

|

Politica de confidentialitate | Termeni si conditii de utilizare |

Vizualizari: 2321

Importanta: ![]()

Termeni si conditii de utilizare | Contact

© SCRIGROUP 2025 . All rights reserved