| CATEGORII DOCUMENTE |

| Bulgara | Ceha slovaca | Croata | Engleza | Estona | Finlandeza | Franceza |

| Germana | Italiana | Letona | Lituaniana | Maghiara | Olandeza | Poloneza |

| Sarba | Slovena | Spaniola | Suedeza | Turca | Ucraineana |

The Rise of the Merchant, Industrialist, and Capital Controller

From

the fifteenth century on, European soldiers and sailors carried the flags of their rulers to

the four corners of the globe, and European merchants established their storehouses from Vera Cruz to

Eric

Wolf,

When I think of Indonesiaa country on the Equator with 180 million people, a median age of 18, and a Moslem ban on alcoholI feel I know what heaven looks like.

Donald R. Keough, President of Coca-Cola

At no other time in human history has the world been a better place for capitalists. We live in a world full of investment opportunitiescompanies, banks, funds, bonds, securities, and even countriesinto which we can put money and from which we can get more back. These money-making machines, such as the Nike Corporation, have a ready supply of cheap labor, capital, raw materials, and advanced technology to assist in making products that people all over the world clamor to buy. Moreover, governments compete for their presence, passing laws and making treaties to open markets, while maintaining infrastructures (roads, airports, power utilities, monetary systems, communication networks, etc.) that enable them to manufacture products or provide services cheaply and charge prices that remain competitive with other investments. Nation-states maintain armies to protect

investments and see that markets

remain open. Educational institutions devote themselves to producing

knowledgeable, skilled, and disciplined workers, while researchers at colleges and

universities develop new technologies to make even better and cheaper products.

Our governments, educational institutions, and mass media encourage people

to consume more and more commodities. Citizens arrange their economic

and social lives to accommodate work in the investment machines and to gain

access to the commodities they produce. In return the investment machines

churn out profits that are reinvested to manufacture more of their

particular products or that can be invested in other enterprises, producing yet

more goods and services. Never before have people had so much opportunity to

accumulate great wealth. Among the 400 richest Americans in 1999, 298 of them

were worth a billion dollars or more, and the top 400 had a net worth of $1.2

trillion, about one-eighth of the total gross domestic product (GDP) of the

But there are economic, environmental, and social consequences of doing business and making money. We live in a world in which the gap between the rich and poor is growing, a world that contains many wealthy and comfortable people and over one billion hungry people, almost one-fifth of its population. Then there are the environmental consequences of doing business: Production uses up the earth's energy resources and produces damaged environments in return. There are health consequences as well, not only from damaged environments but also because those too poor to afford health care often do without it. Finally there are the political consequences of governments' using their armed force to maintain conditions that they believe are favorable for business and investors.

In the long view of human history these conditions are very recent ones. For most of human history human beings have lived in small, relatively isolated settlements that rarely exceeded three or four hundred individuals. And until some ten thousand years ago virtually all of these people lived by gathering and hunting. Then in some areas of the world, instead of depending on the natural growth of plant foods and the natural growth and movements of animals, people began to plant and harvest crops and raise animals themselves. This was not necessarily an advance in human societiesin fact, in terms of labor, it required human beings to do the work that had been done largely by nature. The sole advantage of working harder was that the additional labor supported denser populations. Settlements grew in size until thousands rather than hundreds lived together in towns and cities. Occupational specialization developed, necessitating trade and communication between villages, towns, cities, and regions. Political complexity increased; chiefs became kings, and kings became emperors ruling over vast regions.

Then,

approximately four or five hundred years ago, patterns of travel and communication

contributed to the globalization of trade dominated by 'a small peninsula

off the landmass of Asia,' as Eric Wolf called

Now let's shift our focus to the development of the capitalistthe merchant, industrialist, and financierthe person who controls the capital, employs the laborers, and profits from the consumption of commodities. This will be a long-term, historical look at this development, because if we are to understand the global distribution of power and money that exists today and the origins of the culture of capitalism, knowledge of its history is crucial.

Assume for a time the role of a businessperson, a global merchant, or merchant adventurer, as they used to be called,' passing through the world of the last six hundred years. We'll begin searching the globe for ways to make money in the year 1400 and end our search in the year 2000, taking stock of the changes in the organization and distribution of capital that have occurred in that time. Because we are looking at the world through the eyes of a merchant, there is much that we will missmany political developments, religious wars, revolutions, natural catastrophes, and the like. Because we overlook these events does not mean they did not affect how business was conductedin many cases they had profound effects. But our prime concern is with the events that most directly influenced the way in which business was conducted on a day-to-day basis and how the pursuit of profit by merchant adventurers influenced the lives of people all over the world.

Our historical tour will concentrate on three areas:

An understanding of how capital came to be

concentrated in so few hands and how

the

world came to be divided into rich and poor. There were certainly rich people

and

poor people in 1400, but today's vast global disparity between core and periph

ery did not exist

then. How did the distribution of wealth change, and how did one

area of the world come to dominate the others economically?

An understanding of the changes in

business organizations and the organization of

capital, that is, who controlled the money? In 1400, most business

enterprises were

small, generally family-organized

institutions. Capital was controlled by these

groups and state organizations. Today

we live in an era of multinational corpora

tions, many whose wealth exceeds

that of most countries. We need to trace the evo

lution of the power of capital over our lives and the transformation of the

merchant

of 1400 into the industrialist of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries then

into the

investor and capital controller of the late twentieth century. How and why

did these

transformations in the organization of capital come about?

The increase in the level of global

economic integration. From your perspective as

a merchant adventurer, you obviously want

the fewest restraints possible on your

ability to trade from one area of the

world to another; the fewer restrictions, the

greater the opportunity for profit.

Such things as a global currency, agreement

among nations on import and export

regulations, ease of passage of money and

goods from area to area, freedom to employ whom you want and to pay the

lowest

possible wage are all to your advantage; furthermore, you want few or no govern

ment restrictions regarding the consequences

of your business activities. How did

'The name is taken from a sixteenth-century English trading company, The Merchant Adventurers, cloth wholesalers trading to Holland and Germany with bases of operation in Antwerp and Bergen-op-Zoom and later Hamburg. The company survived until 1809.

the level of global economic integration increase, and what were the consequences for the merchant adventurer, as well as others?

With these questions in mind, let's go back to the world of 1400 and start trading.

The Era of the Global Trader

A Trader's Tour of the World in 1400

|

|

|

The splendor and

wealth of fifteenth- and sixteenth-century |

If, as global merchants in 1400,

we were searching for ways to make money, the best opportunities would be in

long-distance trade, buying goods in one area of the world and selling them in another (see Braudel 1982:68). If

we could choose which among the great cities of the world

and grenades. Cannons were in use by 1300, some mounted on the ships of the Chinese navy, and by the fourteenth century the Chinese were using a metaled-barreled gun that shot explosive pellets (Abu-Lughod 1989:322ff).

If you were to

tour the Chinese countryside you would have been struck by the networks of canals

and irrigation ditches that criss-crossed the landscape, maintained by wealthy landowners or the state.

The economic

conditions in

The city of

The city was

a trader's paradise. Inside the city were ten markets as well as tea houses and

restaurants where traders could meet and arrange their business. Outside the

city were a fish market and wholesale markets. Ibn Battuta said it was 'the

largest city on the face of the earth.' Sections of the city contained

concentrations of merchants from all over the world. Jewish and

Christian traders from

and mosques, and muezzins calling

Muslims to noon prayer. The bazaars of Chinese merchants and

artisans were in yet another section. In brief, Hangchow would have been an ideal place to sell merchandise

from Europe, the Middle East, or other parts of

Silk was particularly desired by

foreign traders because its light weight and compactness made it easy to

transport and because

Your next task would be to

arrange to transport your goods to where you planned to sell them.

Let's assume you had orders from merchants in cities such as

pack trainscamels over the

deserts, mules through the mountains, ox carts where roads existed, human carriers, and boats.

The overland route was popular in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when the Mongols had through their conquests

unified

A safer route in 1400 would have been the sea route, down the East Coast of China, through the Strait of Malacca to Southern India, and then either through the Persian Gulf to Iran and overland, through Baghdad to the Mediterranean, or through the Red Sea to Cairo, and finally by ship to Italy.

Traveling through the Strait of

Malacca and into

From Malacca

you probably would have traveled along the coast of Southeast Asia and on to

From

Leaving East

Africa you would have journeyed up the coast through the Red Sea to

bankers who changed money, took deposits, and issued promissory notes, another way of extending credit and making loans. Merchants kept their accounts by listing credits and debits. Thus all the rudiments of a sophisticated economycapital, credit, banking, money, and account keepingwere present in Islamic trade (Abu-Lughod 1989:216ff).

From

You might then

join other merchants from Genoa, Pisa, and Milan who formed caravans to take

goods such as silks and spices from the Orient or the Middle East, alum, wax, leather,

and fur from Africa, dates, figs, and honey from Spain, and pepper, feathers, and

brazilwood from the Middle East, over the Alps to the fairs and markets of

Western and Northern Europe, a trip taking five weeks. Or you could send your

goods by ship, through

the Mediterranean and the North Sea to trading centers such as

Once you

reached Northern or

Feudalism was

still the main form of political and economic organization in

Woolen

textiles were the most important products of Northern and

Let's assume

you have sold the commodities you brought from

buy Flemish textiles in

What if you

had been able to cross the sea to the

The Inca were just beginning their expansion, which would produce the Andean Empire confronted by Pizarro in 1532. Inca society in 1400 was dominated by the Inca dynasty, an aristocracy consisting of relatives of the ruling group, local rulers who submitted to Inca rule. Men of local rank headed endogamous patrilineal clans, or ayllus, groups who traced descent to a common male ancestor and who were required to marry within their clan. These groups paid tribute to the Inca aristocracy by working on public projects or in military service. Women spent much of their time weaving cloth used to repay faithful subjects and imbued with extraordinary ritual and ceremonial value. The state expanded by colonizing new agricultural lands to grow maize. It maintained irrigation systems, roads, and a postal service in which runners carried information from one end Of the empire to another. Groups that rebelled against Inca rule were usually relocated far from their homeland (Wolf 1982:62-63).

If you had

traveled into the Brazilian rainforests you might have encountered peoples

such as the Tupinamba, who lived on small garden plots while gathering and

hunting in the forests. Sixteenth-century traveler Calvinist pastor Jean de

Lery, concluded that the Tupinamba lived more comfortably than ordinary people

in

In

River. On the surrounding

prairies you would have encountered the peoples of the North-west, the buffalo

hunters of the plains (the horse, often associated with the Plains Indians, wouldn't

arrive for another century), and the Inuit hunters of the

As we complete

our global tour, the barriers to commerce are striking. For example, most political

rulers were not yet committed to encouraging trade. While states might value trade

for the taxes, tolls, and rents they could extract from traders, merchants were

still looked down upon. Rulers generally viewed trade only as a way to gain

profit from traders and merchants, and some states even attempted to control

some trade themselves. In

Geography was obviously a major barrier: trade circuits might take years to complete. Roads were few and ships relatively small and at the mercy of winds and tides. Security was a problem: a merchants' goods were liable to be seized or stolen, or merchants might be forced to pay tribute to rulers along the way.

Economically

there were various restrictions. We were a long way in 1400 from anything

resembling a consumer economy. Most of the world's population lived on a subsistence

economy, that is, produced themselves whatever they needed to exist. In

Thus, overall

the world of 1400 seemed little affected by trade.

The Economic Rise of Europe and Its Impact on Africa and the

Two events dominate the story of the expansion of

trade after 1400: the increased withdrawal

of

nance from a country of one

hundred million occupying most of Asia to a country of one million occupying an area just

slightly larger than the state of

The date and

reason for

Technological advances in boat

building were partially responsible for

Equally

important for

It was the

era of discovery and conquest, of the voyages of

Much is made in

popular culture and history books of the spirit of adventure of early 'explorers' such as

Marco Polo, Vasco da Gama, and Christopher Columbus. But they were less explorers

than merchant sailors. Their motivation was largely economic; they were seeking alternative ways to the riches

of

If you were a

global trader in the sixteenth century and if your starting point were

Let's assume

you have the capital to hire a ship to carry yourself and your goods to

Africans were already producing the

same things as Europeansiron and steel (possibly

the best in the world at the time), elaborate textiles, and other goods. As a

trader, you would have been

interested in the textiles made in Africa, which were in demand in

The institution of slavery goes

back well into antiquity. The ancient Greeks kept slaves, and slave labor was

used throughout the Middle East and

The nature of the slave trade has

long been a contentious issue among historians. Many believe the slave trade was forced on

Slaves were

regarded traditionally in Africa as subordinate family members, as they were in

The size of African states may have reflected the lack of concern with land as property. John Thornton (1992:106) estimated that only 30 percent of Atlantic Africa con-

tained states larger than fifty

thousand square kilometers (roughly the size of

Given these attitudes toward land

and toward labor, there existed in

Once you obtained the slaves, you

might have obtained a special ship to transport them back to Europe or to one of the

Let's assume that after buying

slaves in Africa and selling them in the new sugar plantations of the Azores,

you resume your journey and go west to the

At the time

of the conquest of the

Most of the silver came from

The amount of

currency in circulation worldwide increased enormously, enriching Europe but

eroding the wealth of other areas, and helping

Gold and

silver were not the only wealth extracted from the

The cost of the European expansion

of trade to the

There is broad

disagreement about the population of the

There is

little doubt, we think, that the higher estimates are closer to the actual population of the

In 1496 Bartolome Colon,

Christopher's brother, authorized a headcount of adults of Espanola, the present day Haiti and Dominican Republic, then the most

populous of the Caribbean Islands. The people of the island, the Tainos,

created a culture that extended over

most of the

The scale of

death after the arrival of the Europeans is difficult to conceive and rivals any estimate

made for the demographic consequences of a nuclear holocaust today. When the

Spanish surveyed Espanola in 1508, 1510, 1514, and 1518, they found a

population of under one hundred thousand. The most detailed of the surveys,

taken in 1514, listed just 22,000 adults, which anthropologists Sherburne Cook

and Woodrow Borah estimated to represent a total population of 27,800 (Cook

and Borah, 1960). Thus in just over twenty years there was a decline from

at least 2 million to 27,800 people. Bartolome de Las Casas, the major

chronicler of the effects of the Spanish invasion, said that by 1542 there were

just two hundred indigenous Tainos left, and within a decade they were

extinct. Cook and Borah concluded that in

Many died in battles with the invaders; others were murdered by European occupiers desperate to maintain control over a threatening population; and still others died as a result of slavery and forced labor. But the vast majority died of diseases introduced by Europeans to which the indigenous peoples had no immunity.

The most deadly of the diseases was

smallpox. It arrived sometime between 1520 and

1524 with a European soldier or sailor and quickly spread across the continent,

ahead of the advancing Europeans. When Pizarro reached the Inca in 1532,

his defeat of a divided Empire was made

possible by the death from smallpox of the ruler and the crown prince. When a Spanish expedition set out from

Dobyns (1983:13-14; see also Stiffarm and Lane 1992) estimated that in the epidemic of 1520-1524 virtually all indigenous peoplescertainly those in large population areaswould have been exposed to smallpox, and since there would have been no immunity the death rate, judging by known death rates among other Native American populations, must have been at least 60-70 percent. Spanish reports of the time that half of the native population died, said Dobyns, most certainly were underestimates.

This was not the only smallpox epidemic. Dobyns calculated that there were forty-one smallpox epidemics in North America from 1520 to 1899, seventeen measles epidemics from 1531 to 1892, ten major influenza epidemics from 1559 to 1918, and four plague epidemics from 1545 to 1707, to name a few. In all, he said, a serious epidemic invaded indigenous populations on average every four years and two and half months during the years 1520-1900.

Thus the

occupation of the

In 1776, Adam

Smith, in The Wealth of Nations, wrote, 'The discovery of

A decade later

there was a debate among the savants of

Let us stop here, and consider

ourselves as existing at the time when

The Rise of the Trading Companies

The expansion of trade into the

The seventeenth century marked the era of what economists call mercantilism, as European states did all they could to protect, encourage, and expand industry and trade, not for its own sake but to prevent wealth, largely in the form of gold and silver, from leaving their countries. States enacted protective legislation to keep out foreign goods and to prevent gold and silver from leaving, and they subsidized the growth of selected industries by ensuring the existence of a cheap labor supply. Also during the seventeenth-century the so-called trading or joint stock company evolved, a joining of trade and armed force designed to ensure the continued extraction of wealth from areas around the world.

As a global merchant in 1700 your

best chance of making profits would have been to

join a trading company, by far the most sophisticated instrument of

state-sponsored trade. The companies consisted of groups of traders,

each of whom invested a certain amount of capital and were given charters by

the state and presented with monopolistic trade

privileges in a particular area of the world. Since other countries also gave

monopolistic trading privileges to

their companies, there was often armed conflict between them. For

example, in 1600 the British crown issued a royal charter to the Governor and

the Company of Merchants of London trading

with the

The Dutch

maintained political control over its posts in

Other trading

companies granted charters by the British state include the Virginia Company in

1606, the English Amazon Company in 1619, the Massachusetts Company in 1629,

the Royal Adventurers into Africa in 1660, and the

The Dutch were

initially best able to exploit the new developments in trade, largely because of their large merchant

fleet and the development of the fluitschip, a light and slender vessel that carried heavy cargoes. The

availability of funds in financial centers such as Antwerp and

Amsterdam, much of it originating in the gold and silver of the Americas, allowed builders to get the best woods

and best craftsmen and employ foreign sailors.

Gradually, however,

As a merchant adventurer in the first

part of the eighteenth century you may have joined the Virginia Company and

established a trading post, or 'factory,' in southern Ap-palachia, probably in a Cherokee

village. The Cherokee were necessary to supply the commodities you would want to acquire for trade, items such as

deerskins, ginseng and other herbs in demand in

Prior to European contact the Cherokee lived in large towns in which land was owned communally, and subsistence activities consisted of hunting, fishing, gathering, and agriculture. The Cherokee population had been decimated by disease by the early eighteenth century, but they still retained most of their traditional culture. For example, Cherokee villages were relatively independent from each other, each having its own leaders and each relatively self-sufficient in food and production of necessities such as clothing, weapons, and cooking utensils. The independence of village leaders, however, made it difficult for the British government and traders to deal with the Cherokee. If there were overall leaders who could make agreements binding on large groups, with whom government and merchants could deal, it would be far easier to make treaties, collect trade debts, and engineer political alliances (Dunaway 1996:31). Consequently, using their military power and the threat of withdrawing trade, the British government appointed chiefs who they recognized as having the power to make agreements binding on the entire Cherokee nation whether or not their autonomy was recognized by other Cherokee. The British government also encouraged conflict between indigenous groups, reasoning, as the South

Thus merchants, such as yourself,

along with the Cherokee, became integrated into a global trade network in which slaves and deerskins were sent through

For traders,

these arrangements worked very well: by 1710 as many as 12,000 Indians had

been exported as slaves and by 1730 some 255,000 deerskins were being shipped annually from British trading posts

to

But what of the Cherokee? By becoming integrated into the global economy on terms dictated by British government officials and traders, the Cherokee economy was transformed from self-sufficient agricultural production to a 'putting-out' system in which they were given the tools for production (e.g., guns) along with an advance of goods in exchange for their laboran arrangement that destroyed traditional activities and stimulated debt peonage. To pay off debts accumulated to acquire European goods, communal Cherokee land was sold by chiefs appointed by the British: in little more than fifty years the British extinguished title to about 57 percent of the Cherokee traditional land (some 43.9 million acres).

In addition, the new economy brought profound changes in Cherokee social life. Trade was male-oriented, men being responsible for acquiring the itemsslaves and deerdesired by the British. This removed men from traditional agricultural activities as well as incapacitating them with rum (Dunaway 1996:37). By the mid-1700s, British observers noted that 'women alone do all the laborious tasks of agriculture,' freeing men to hunt or go to war.

Furthermore, traditional crafts deteriorated with the increased consumption of European goods such as guns, axes, knives, beads, pottery, clothing, and cooking utensils. By the mid-1700s the British could report that 'the Indians by reason of our supplying them so cheap with every sort of goods, have forgotten the chief part of their ancient mechanical skill, so as not to be able now, at least for some years, to live independent from us' (Dunaway 1996:38). In 1751, the Cherokee chief Skiagonota would observe that 'the clothes we wear we cannot make ourselves. They are made for us. We use their ammunition with which to kill deer. We cannot make our guns. Every necessity of life we have from the white people' (cited Dunaway 1996:39).

The Era of the Industrialist

By 1800,

largely by the growth of industry, particularly

textiles, and the related increase in the availability

of cheap labor. And while the British lost her American coloniespolitically if

not economicallyshe gained in many ways a wealthier prize

But the big news was the industrial

development of

Social

scientists often pose the related questions, what made

The reasons

for the industrial revolution in

An increase in demand for goods. This demand may have

been foreign or domestic,

supplemented

by increased demands for largely military products from the state. The

tile industry was

revolutionary also in its organization of labor and its relationship to the

foreign market, on which it depended for

both raw materials (in the case of cotton) and

markets. Historian Eric Hobsbawm argued that there was room for only one world

sup

plier, and that ended up being

The increase

in the supply of capital. An increase in trade resulted in greater profits

and

more money, and these profits supplied the capital for investment in new

technologies

and

businesses.

A growth in population. Population

increased dramatically in

in the eighteenth century. From 1550 to 1680 the population of

18 percent and from 1680 to 1820 by 62

percent. From 1750 to 1850

tion increased from 5.7 million to

16.5 million. Population increase was important be

cause it increased the potential labor

force and the number of potential consumers of

commodities. But there is disagreement as to why population increased

and the effects it

had on industrialization.

Some account

for the increase with lower mortality rates attributable to smallpox inoculation

and an improved diet related to the introduction of new foodstuffs, such as the

potato. Life expectancy at birth went from thirty-five to forty years (Guttmann

1988:130). Others attribute the rise in population to an increase in fertility.

Indeed, families were larger

in the eighteenth century. In

An expansion of agriculture. There

was an expansion of agricultural production in

squatters and peasants from common

lands and forests from which they had drawn a liveli

hood. The rationale was to turn those

lands over to the gentry to make them more produc

tive, but this also had the effect of producing a larger landless and

propertyless population,

dependent on whatever wage labor they

might find. Regardless, some argue that the in

creased agricultural yields allowed

the maintenance of a larger urban workforce.

A unique English

culture or spirit. Some, notably sociologist Max Weber, attribute

the rise of

ethic, that motivated

people to business success in the belief that it would reveal to them

whether they were among God's elect.

State support

for trade. Some claim that a more liberal state structure imposed

fewer

taxes and regulations on businesses, thus allowing them to thrive. The state

did take

action

to support trade and industry. There was continued political and military

support

for

extending

chants from labor protest. A law of 1769 made the destruction of machines and

the build

ings

that housed them a capital crime. Troops were sent to put down labor riots in

Lancaster

in 1779 and in Yorkshire in 1796, and a law passed in 1799 outlawed worker

associations that

sought wage increases, reduction in the working day, 'or any other im

provement in the conditions of employment or work' (Beaud 1983:67).

The

ascendance of the merchant class. Stephen Sanderson (1995) attributed the de

velopment

of capitalism to an increase in the power of the merchant class. There has

always been, he suggested, competition between merchants and the ruling elites,

and

while

elites needed merchants to supply desired goods and services, they nevertheless

looked

down on them. But gradually the economic power of the merchant class grew

until,

in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the merchant emerged as the most

pow

erful member of

Western, capitalist society. Capitalism, said Sanderson (1995:175-176),

'was born of a class struggle.

However, it was not, as the Marxists would have it, a strug

gle between landlords and peasants. Rather, it was a struggle between

the landlord class

and the merchants that was fundamental in the rise of capitalism.'

A revolution

in consumption. Finally, some attribute the rapid economic growth in

in the number of stores and shops and the

beginning of a marketing revolution, led by the

pottery industry and the

entrepreneurial genius of Josiah Wedgewood, who named his

pottery styles after members of the Royal Family to appeal to the

fashion consciousness

of the rising middle class.

Regardless of the reasons for England's rise and the so-called industrial revolution, there is little doubt that in addition to the traditional means of accumulating wealthmercantile trade, extracting the surplus from peasant labor, pillage, forced labor, slavery, and taxes a new form of capital formation increased in importance. It involved purchasing and combining the means of production and labor power to produce commodities, the form of wealth formation called capitalism that we diagramed earlier as follows: M >C >mp/lp >C' >M

[Money is converted to commodities (capital goods) that are combined with the means of production and labor power to produce other commodities (consumer goods), that are then sold for a sum greater than the initial investment]. How did this mode of production differ from what went before ?

Eric Wolf offered one of the more concise views. For capitalism to exist, he said, wealth or money must be able to purchase labor power. But as long as people have access to the means of productionland, raw materials, tools (e.g., weaving looms, mills) there is no reason for them to sell their labor. They can still sell the product of their labor. For the capitalistic mode of production to exist, the tie between producers and the means of production must be cut; peasants must lose control of their land, artisans control of their tools. These people, once denied access to the means of production, must negotiate with those who control the means of production for permission to use the land and tools and receive a wage in return. Those who control the means of production also control the goods that are produced, and so those who labor to produce them must buy them back from those with the means of production. Thus the severing of persons from the means of production turns them not only into laborers but into consumers of the product of their labor as well. Here is how Wolf (1982:78-79) summarized it:

Wealth in the hands of holders of wealth is not capital until it controls means of production, buys labor power, and puts it to work continuously expanding surpluses by intensifying production through an ever-rising curve of technological inputs. To this end capitalism must lay hold of production, must invade the productive process and ceaselessly alter the conditions of production themselves. Only where wealth has laid hold of the conditions of production in ways specified can we speak of the existence or dominance of a capitalistic mode. There is no such thing as mercantile of merchant capitalism, therefore. There is only mercantile wealth. Capitalism, to be capitalism, must be capitalism-in-production.

Wolf (1982:100) added that the state is central in developing the capitalist mode of production because it must use its power to maintain and guarantee the ownership of the means of production by capitalists both at home and abroad and must support the organization and discipline of work. The state also has to provide the infrastructure, such as transportation, communication, judicial system, and education, required by capitalist production. Finally, the state must regulate conflicts between competing capitalists both at home and abroad, by diplomacy if possible, by war if necessary.

The major

questions are how did this industrially driven, capitalist mode of

production evolve, and what consequences did it have in

Textiles and the Rise of the Factory System

Assume once again your role as a

textile merchant; let's examine the opportunities and problems confronting you

as you conduct business. Typical textile merchants of the early eighteenth

century purchased their wares from specialized weavers or part-time producers

of cloth or from drapers, persons who organized the production of cloth but did

not trade in it. The merchant then sold the cloth to a consumer or another

merchant who sold it in other areas of

It does not require a large capital outlay for the merchant, since the artisan has the tools and material he or she needs, and as long as there is a demand for the cloth there is someone who will buy it.

But as a merchant you face a couple of problems. First, the people who make the cloth you buy may not produce the quantity or quality that you need, especially as an expanding population begins to require more textiles. Moreover, the artisan may have trouble acquiring raw materials, such as wool or cotton, further disrupting the supply. What can you do?

One thing to

do is to increase control over what is produced by 'putting out'sup-plying the

drapers or weavers with the raw materials to produce the clothor, if you have the capital, buy toolslooms,

spinning wheels, and so onand give them to people to make the cloth, paying

them for what they produce. Cottage industry of this sort was widespread throughout

|

|

|

Power loom weaving in a cotton textile factory in 1834. Note that virtually all the workers are women. |

Another

problem English textile merchants faced in the mid-eighteenth century was that the textile business,

especially in cotton, faced stiff competition from

industry to satisfy domestic demand. This not only

helped protect the British textile industry,

it virtually destroyed the Indian cotton industry, and before long

We have excluded the manufactures

of

And in 1840,

the chairman of

that This Company has, in various ways, encouraged and assisted by our great manufacturing ingenuity and skill, succeeded in converting India from a manufacturing country into a country exporting raw materials, (cited Wallerstein 1989:150)

The next, and to some extent inevitable, stage in textile production was to bring together in one placethe factoryas many of the textiles production phases as possible: preparing the raw wool or cotton, spinning the cotton yarn and wool, weaving the cloth, and applying the finishing touches. This allowed the merchant or industrialist to control the quantity and quality of the product and control the use of materials and tools. The only drawback to the factory system is that it is capital-intensive; the merchant was now responsible for financing the entire process, while the workers supplied only their labor. Most of the increase in cost was a consequence of increased mechanization.

Mechanization of the textile industry began with the invention by John Kay in 1733 of the flying shuttle, a device that allowed the weaver to strike the shuttle carrying the thread from one side of the loom to the other, rather than weaving it through by hand. This greatly speeded up the weaving process. However, when demand for textiles, particularly cotton, increased, the spinning of thread, still done on spinning wheels or spindles, could not keep up with weavers, and bottlenecks developed in production. To meet this need James Hargreaves introduced the spinning jenny in 1770. Later, Arkwright introduced the water frame, and in 1779 Crompton introduced his 'mule' that allowed a single operator to work more than 1,000 spindles at once. In 1790 steam power was supplied. These technological developments increased textiles production enormously: the mechanical advantage of the earliest spinning jennies to hand spinning was twenty-four to one. The spinning wheel had become an antique in a decade (Landes 1969:85). The increase in the supply of yarntwelve times as much cotton was consumed in 1800 than in 1770 required improvements in weaving, which then required more yarn, and so on.

The revolution in production, however, produced other problems. Who was going to buy the increasing quantity of goods that were being produced, and where was the raw material for production to come from?

The Age of Imperialism

The results of the industrial

revolution in

time, the most favorable for

accumulation of vast fortunes through trade and manufacture. Developments in

transportation such as railroads and steamships revolutionized the transport of raw

materials and finished commodities. The combination of new sources of power in water

and steam, a disarmed and plentiful labor force, and control of the production and

markets of much of the rest of the world resulted in dramatic increases in the level of production and wealth.

These advances were most dramatic in

There was also a revolution in

shipping as ocean freight costs fell, first with the advent of the narrow-beamed American clipper ship and later with the

introduction of the steamship. A clipper ship could carry 1,000 tons of freight

and make the journey from the south

coast of

But it was not

all good news for the capitalist economy. There was organized worker

resistance to low wages and impoverished conditions, resistance and rebellion

in the periphery, and

the development of capitalist business cycles that led to worldwide economic depressions. Thus, while business

thrived in much of the nineteenth century, it had also entered a world of great

uncertainty. First, with the expansion of the scope of production, capital

investments had increased enormously. It was no longer possible, as it had been in 1800 when a forty-spindle jenny cost

6, to invest in the factory production of textiles at fairly modest

levels. Furthermore, there was increased competition, with factory production expanding dramatically in

The Great

Global Depression of 1873 that lasted essentially until 1895 was the first great manifestation of the

capitalist business crisis. The depression was not the first economic crisis: For thousands of years there had

been economic declines because of famine, war, and disease. But the

financial collapse of 1873 revealed the degree of global economic integration, and how economic events in one

part of the globe could reverberate in others. The economic depression

began when banks failed in

The Depression of 1873 revealed another big problem with capitalist expansion and perpetual growth: it can continue only as long as there is a ready supply of raw materials and an increasing demand for goods, along with ways to invest profits and capital. Given this situation, if you were an American or European investor in 1873, where would you look for economic expansion?

The obvious

answer was to extend European and American power overseas, particularly into

areas that remained relatively untouched by capitalist expansionAfrica,

I was in the East End of London yesterday and attended a meeting of the unemployed. I listened to the wild speeches, which were just a cry for 'bread,' 'bread,' and on my way home I pondered over the scene and I became more than ever convinced of the importance of imperialism. My cherished idea is a solution for the social problem, i.e., in order to save the 40,000,000 inhabitants of the United Kingdom from a bloody civil war, we colonial statesmen must acquire new lands for settling the surplus population, to provide new markets for the goods produced in the factories and mines. The Empire, as I have always said, is a bread and butter question. If you want to avoid civil war, you must become imperialists, (cited Beaud 1983:139-140)

P. Leroy-Beaulieu voiced the same

sentiments in

It is neither natural nor just that the civilized people of the West should be indefinitely crowded together and stifled in the restricted spaces that were their first homes, that they should accumulate there the wonders of science, art, and civilization, that they should see, for lack of profitable jobs, the interest rate of capital fall further every day for them, and that they should leave perhaps half the world to small groups of ignorant men, who are

powerless, who are truly retarded children dispersed over boundless territories, or else to decrepit populations without energy and without direction, truly old men incapable of any effort, of any organized and far-seeing action, (cited Beaud 1983: 140)

As a result of this cry for imperialist expansion, people all over the world were converted into producers of export crops as millions of subsistence farmers were forced to become wage laborers producing for the market and to purchase from European and American merchants and industrialists, rather than supply for themselves, their basic needs. Nineteenth century British economist William Stanley Jevons (cited Kennedy 1993:9) summed up the situation when he boasted:

The plains of North America and Russia are our cornfields; Chicago and Odessa our granaries; Canada and the Baltic are our timber forests; Australasia contains our sheep farms, and in Argentina and on the western prairies of North America are our herds of oxen; Peru sends her silver, and the gold of South Africa and Australia flows to London; the Hindus and the Chinese grow tea for us, and our coffee, sugar, and spice plantations are all in the Indies. Spain and France are our vineyards and the Mediterranean our fruit garden, and our cotton grounds, which for long have occupied the Southern United States are now being extended everywhere in the warm regions of the earth.

Wheat became the great export crop

of

In 1871 a railroad promoter from the United States built a railroad in Costa Rica and experimented in banana production; out of this emerged in 1889 the United Fruit Company that within thirty-five years was producing two billion bunches of bananas. The company reduced its risk by expanding into different countries and different environments and by acquiring far more land than it could use at any one time as a reserve against the future.

The demand

for rubber that followed the discovery of vulcanization in 1839 led to foreign investments in areas such as

In the nineteenth century palm oil became a substitute for tallow for making soap and a lubricant for machinery, resulting in European military expansion into West Africa and the conquest of the kingdoms of Asante, Dahomey, Oyo, and Benin.

Vast

territories were turned over to the production of stimulants and drugs such as sugar, tea,

coffee, tobacco, opium, and cocoa. In the Mexican state of

owned and subject to purchase,

sale, and pawning, allowing non-Indians to buy unregistered land and foreclose mortgages

on Indian borrowers (Wolf 1982:337). These lands were then turned to coffee production and, later, cattle ranching. In

Colonization was not restricted to overseas areas; it occurred also within the borders of core states. In 1887 the U.S. Congress passed the General Allotment Act (the 'Dawes Act') to break up the collective ownership of land on Indian reservations by assigning each family its own parcel, then opening unallotted land to non-Indian homesteaders, corporations, and the federal government. As a consequence, from 1887 to 1934 some 100 million acres of land assigned by treaty to Indian groups was appropriated by private interests or the government (Jaimes 1992:126).

At first glance it may seem that the growth in development of export goods such as coffee, cotton, sugar, and lumber, would be beneficial to the exporting country, since it brings in revenue. In fact, it represents a type of exploitation called unequal exchange. A country that exports raw or unprocessed materials may gain currency for their sale, but they then lose it if they import processed goods. The reason is that processed goods goods that require additional laborare more costly. Thus a country that exports lumber but does not have the capacity to process it must then re-import it in the form of finished lumber products, at a cost that is greater than the price it received for the raw product. The country that processes the materials gets the added revenue contributed by its laborers.

Then there is

the story of tea and opium and trade in

The British-led opium trade from

Thus, as a merchant adventurer,

your economic fortune has been assured by your government's control over foreign economies. Not only could you make

more money investing in foreign enterprises, but the wealth you

accumulated through trade and manufacturing

gained you entry into a new elite, one with increasing power in the core countries. Power was no longer evidenced solely in

the ownership of land, but in the control of capital. In

In the

The Era of the Corporation, the Multilateral Institution, and the Capital Controller

While the imperialist activities

of the core powers allowed their economies to grow, they also created

international conflict on a scale never before imagined. In 1900, each of the great powers

sought to carve out a sphere of domination in Asia, Africa, and South and

Attempts to

extend or defend these zones of economic influence triggered what was until then

the bloodiest war ever foughtWorld War I. Eight million people were killed.

The

The Rise of the Corporation

From your perspective as a

merchant adventurer, the most important development of the early

twentieth century was the merger frenzy in the

Painter Diego Rivera's depiction of the symbols of corporate wealth as John D. Rockefeller (rear left), J. P. Morgan (rear right), Henry Ford (to Morgan's left), and others read a ticker tape while dining.

become one of the dominant governance units in the world. By 1998 there were more than 53,000 transnational corporations (French 2000:5). From their foreign operations alone they generated almost $6 trillion in sales. The largest corporations exceed in size, power, and wealth most of the world's nation-states and, directly or indirectly, define policy agendas of states and international bodies (Korten 1995:54). Since, as a merchant adventurer, you have now entered the corporate age, what kind of institution is the corporation and how did it come to accumulate so much wealth and power?

Technically a corporation is a social invention of the state; the corporate charter, granted by the state, ideally permits private financial resources to be used for a public purpose. At another level, it allows one or more individuals to apply massive economic and political power to accumulate private wealth while protected from legal liability for the public consequences. As a merchant adventurer, clearly you want to create an institution in which you can increase and protect your own profits from market uncertainties (Korten 1995:53-54).

The corporate charter goes back to the sixteenth century, when any debts accumulated by an individual were inherited by his or her descendants. Consequently, someone could be jailed for the debts of a father, mother, brother, or sister. If you, in your role as merchant adventurer, invested in a trading voyage and the goods were lost at sea, you and your descendants were responsible for the losses incurred. The law, as written, inhibited risky investments. The corporate charter solved this problem because it represented a grant from the crown that limited an investor's liability for losses to the amount of the investment, a right not accorded to individual citizens.

The early

trading companies, such as the East India Company and the

Suspicion of the power of corporations developed soon after their establishment. Even eighteenth-century philosopher and economist Adam Smith, in Wealth of Nations, condemned corporations. He claimed corporations operated to evade the laws of the market by artificially inflating prices and controlling trade. American colonists shared Smith's suspicion of corporations and limited corporate charters to a specific number of years. If the charter was not renewed, the corporation was dissolved. But gradually American courts began to remove restrictions on corporations' operation. The U.S. Civil War was a turning point: corporations used their huge profits from the war, along with the subsequent political confusion and corruption, to buy legislation that gave them huge grants of land and money, much of which they used to build railroads. Abraham Lincoln (cited Korten 1995:58) saw what was happening and just before his death observed:

Corporations have been enthroned. An era of corruption in high places will follow and the money power will endeavor to prolong its reign by working on the prejudices of the people until wealth is aggregated in a few hands and the Republic is destroyed.

Gradually corporations gained control of state legislatures, such as those in Delaware and New Jersey, lobbying for (and buying) legislation that granted charters in perpetuity, limited the liabilities of corporate owners and managers, and gained the right of corporations to operate in any way not specifically prohibited by the law. For example, courts limited corporate liability for accidents to workers, an important development in the nineteenth century when fatal industrial accidents from 1888 to 1908 killed 700,000 workers, or roughly one hundred per day. Other favorable court rulings and legislation prohibited the state from setting minimum wage laws, limiting the number of hours a person could work, or setting minimum age requirements for workers.

A Supreme Court ruling in 1886, however, arguably set the stage for the full-scale development of the culture of capitalism. The court ruled that corporations could use their economic power in a way they never before had. Relying on the Fourteenth Amendment, added to the Constitution in 1868 to protect the rights of freed slaves, the Court ruled that a private corporation is a natural person under the U.S. Constitution, and consequently has the same rights and protection extended to persons by the Bill of Rights, including the right of free speech. Thus corporations were given the same 'rights' to influence the government in their own interest as were extended to individual citizens, paving the way for corporations to use their wealth to dominate public thought and discourse. The debates in the United States in the 1990s over campaign finance reform, in which corporate bodies can 'donate' millions of dollars to political candidates, stem from this ruling, although rarely if ever is that mentioned. Thus corporations, as 'persons,' were free to lobby legislatures, use the mass media, establish educational institutions such as the many business schools founded by corporate leaders in the early twentieth century, found charitable organizations to convince the public of their lofty intent, and in general construct an image that they believed would be in their best interests. All of this in the interest of 'free speech.'

Corporations used this power, of course, to create conditions in which they could make more money. But in a larger sense they used this power to define the ideology or ethos of the emerging culture of capitalism. This cultural and economic ideology is known as neoclassical, neoliberal, or libertarian economics, market capitalism, or market liberalism and is advocated in society primarily by three groups of spokespersons: economic rationalists, market liberals, and members of the corporate class. Their advocacy of these principles created what David Korten called corporate libertarianism, which places the rights and freedoms of corporations above the rights and freedoms of individualsthe corporation comes to exist as a separate entity with its own internal logic and rules. Some of the principles and assumptions of this ideology include the following.

Sustained economic growth, as measured by gross

national product (GNP), is the

path to human

progress.

Free markets, unrestrained

by government, generally result in the most efficient and

socially optimal

allocation of resources.

Economic

globalization, achieved by removing barriers to the free flow of

goods

and

money anywhere in the world, spurs competition, increases economic effi

ciency, creates jobs,

lowers consumer prices, increases consumer choice, increases

economic growth, and is generally beneficial to almost everyone.

Privatization,

which moves functions and assets from governments to the private

sector,

improves efficiency.

The primary

responsibility of government is to provide the infrastructure necessary

to

advance commerce and enforce the rule of law with respect to property rights

and contracts.

Hidden in these principles, however, said Korten, are a number of questionable assumptions. First, there is the assumption that humans are motivated by self-interest, which is expressed primarily through the quest for financial gain (or, people are by nature motivated primarily by greed). Second, there is the assumption that the action that yields the greatest financial return to the individual or firm is the one that is most beneficial to society (or, the drive to acquire is the highest expression of what it means to be human). Third, is the assumption that competitive behavior is more rational for the individual and the firm than cooperative behavior; consequently, societies should be built around the competitive motive (or, the relentless pursuit of greed and acquisition leads to socially optimal outcomes). Finally, there is the assumption that human progress is best measured by increases in the value of what the members of society consume, and ever-higher levels of consumer spending advance the well-being of society by stimulating greater economic output (or, it is in the best interest of human societies to encourage, honor, and reward the above values).

While corporate libertarianism has its detractors, from the standpoint of overall economic growth few can argue with its success on a global scale. World economic output has increased from $6.7 trillion in 1950 to over $41.6 trillion in 1998. Economic growth in each decade of the last half of the twentieth century was greater than the economic output in all of human history up to 1950. World trade has increased from total exports of $308 billion in 1950 to $5.4 trillion in 1998. In 1950 world exports of goods was only 5% of the world GNP; by 1998 this figure was 13% (French 2000:5)

There were still, however, some

problems for the merchant adventurer in the early twentieth century. As

corporations rose to power in the 1920s and 1930s, political and business leaders were aware that corporations, by

themselves, could not ensure the smooth

running of the global economy. The worldwide economic depression of the 1930s

and the economic disruptions caused by World War II illustrated that. That

every country had its own currency and that it could rapidly rise or fall in

value relative to others created barriers

to trade. Tariffs and import or export laws inhibited the free flow of goods

and capital. More important, there was the problem of bringing the ideology of

corporate libertarianism, and the culture of capitalism in general, to the

periphery, especially given the challenge

of socialism and the increasing demands of colonized countries for independence. The solution to these problems was to

emerge from a meeting in 1944 at a

Bretton Woods and the World Debt

In 1944 President Franklin D. Roosevelt gathered the

government financial leaders of forty-four

nations to a meeting at the Mt. Washington Hotel in

far-reaching events of the twentieth century. The meeting was called ostensibly to rebuild war-ravaged economies and to outline a global economic agenda for the last half of the twentieth century. Out of that meeting came the plan for the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (The World Bank), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to control currency exchange, and the framework for a worldwide trade organization that would lead to the establishment in 1948 of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) to regulate trade between member countries. While GATT was not as comprehensive an agreement as many traders would have liked, its scope was widely enlarged on January 1, 1995, with the establishment of the World Trade Organization (WTO). The functions of these agencies are summarized in Table 3.1.

The IMF constituted an agreement by the major nations to allow their currency to be exchanged for other currencies with a minimum of restriction, to inform representatives of the IMF of changes in monetary and financial policies, and to adjust these policies to accommodate to other member nations when possible. The IMF also has funds that it can lend to member nations if they face a debt crisis. For example, if a member country finds it is importing goods at a much higher rate than it is exporting them, and if it doesn't have the money to make up the difference, the IMF will arrange a short-term loan (Driscoll 1992:5).

The World

Bank was created to finance the reconstruction of Europe after the devastation of World War II, but the

only European country to receive a loan was

The GATT has

served as a forum for participating countries to negotiate trade policy. The

goal was to establish a multilateral agency with the power to regulate and

promote free trade among nations. However, since legislators and government officials

in many countries, particularly the

TABLE 3.1

The Bretton Woods Institutions

Institution

or Agency Function

![]() International

Monetary Fund (IMF) To make funds

available for countries to meet short-term financial needs and to stabilize

currency exchanges between countries

International

Monetary Fund (IMF) To make funds

available for countries to meet short-term financial needs and to stabilize

currency exchanges between countries

International Bank for Reconstruction To make loans for various development projects and Development (World Bank)

General Agreement on Tariffs and To ensure the free trade of commodities among

Trade (GATT) countries

growth hormones. These hormones

are manufactured in the

The year 1994 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the Bretton Woods institutions, prompting a worldwide review of their successes and failures. Generally the reviews were not favorable, leading, as we shall see in Chapter 13, to widespread protests and demonstrations against the World Bank, the IMF, and the WTO. Even the World Bank's own evaluations were highly critical of its performance. In spite of lending some quarter of a trillion dollars to peripheral countries, one billion people in the world are desperately poor; furthermore, the disparity of wealth in the world between the core and periphery has doubled in the last thirty years. The richest 20 percent of the world's people now consume 150 times more of the world's goods than the poorest 20 percent (United Nations 1993:11).

One of the most profound influences of the Bretton Woods meeting is the accumulation of the debt of peripheral countries; some consider this 'debt crisis' the gravest one facing the world. The reasons for the debt crisis, and the possible impact it can have on everyone's lives, is complex but essential to understand. Overwhelming debt of peripheral countries is one of the major factors in many global problems that we will explore, including poverty, hunger, environmental devastation, the spread of disease, and political unrest.

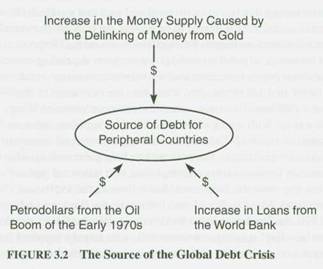

Three things were particularly important in creating the debt crisis: the change over the last third of this century in the meaning of money; the amount of money lent by the World Bank and other lending institutions to peripheral countries; and the oil boom of the early 1970s and the pressure for financial institutions to invest that money.

Money, as noted in Chapter 1, constitutes the focal point of capitalism. It is through money that we assign value to objects, behaviors, and even people. The fact that one item can, in various quantities, represent virtually any item or service, from a soft drink to an entire forest, is one of the most remarkable features of our lives. But it is not without its problems. The facts that different countries have different currencies and that currencies can rise or fall in value relative to the goods they can purchase have always been a barrier to unrestricted foreign trade and global economic integration. Furthermore, there have always been disputes concerning how to measure the value of money itself. Historically money has been tied to a specific valuable metal, generally gold. Thus money in any country could always be redeemed for a certain amount of gold, although the amount could vary according to the value of a specific country's currency.

While the

meeting at Bretton Woods would not lead to the establishment of a global currency, the

countries did agree to exchange their currency for U.S. dollars at a fixed rate, while the

Since countries no longer needed to have a certain amount of gold in order to print money, money became more plentiful. How this happened, and the impact it has had on all our lives requires some elaboration.

We generally assume that governments create money by printing it. And, in fact, when money was linked to gold, there was a limit on how much could be printed. However, with the lifting of these restrictions, most money is now created by banks and other lending institutions through debt. We generally assume also, that the money that banks lend is money that others have deposited. However that is not the case; only a fraction of the money that banks lend needs to be in deposits. In effect, whenever a bank lends money, or whenever a product or service is purchased on credit, money has been created. In effect, then, there is virtually no limit on the amount of money that lending institutions can create; furthermore, the interest on the loan payments creates yet more money. To get an idea of what this means, in the United Kingdom in 1997 the total money stockcoins, notes, deposits, loans, etc.amounted to 680 billion (it was only 14 billion in 1963). Yet there was actually only 25 billion in actual coins and notes (Rowbotham 1998: 12-13). Thus 97% of the money had been created by banks and other lending institutions. Economists call this 'debt money' (Rowbotham 1998:5), or 'credit money' (Guttmann 1994).

Debt provides an important service to the culture of capitalism; it allows people to buy things with money they don't havethereby fueling economic growthand it requires people to work in order to pay off their debts. Furthermore it stimulates greater need for economic growth to maintain interest ratesthat is return on investments. It also means, however, that there is more money that has to be invested and lent, and a considerable amount of that went to peripheral countries. This proved to be a boon, not only for individual borrowers but also for peripheral countries seeking to develop their economies. The problems were that the interest on most loans was adjustable (could go up or down depending on economic circumstances) and that debts began to accumulate beyond what countries could repay.

The second factor that led to the

debt crisis was the operation of the World Bank. The Bank itself had a problem. European countries, whose economies it

was to help rebuild, didn't need the help. With a lack of demand for their

services, what could they do? How could the institution survive? The Bank's

solution was to lend money to peripheral countries to develop their economies.

The plan was to help them industrialize by funding things such as large-scale hydroelectric projects,

roads, and industrial parks. Furthermore, the bigger the project, the more the Bank could lend; thus, in the

1950s and 1960s money suddenly poured

into

But the success of the Bank in lending money created another problemwhat economists call net negative transfers; borrowing nations collectively were soon paying more money into the Bank than the Bank was lending out. Put another way, the poor or peripheral nations were paying more money to the rich core nations than they were receiving from them. Aside from the consequences for poor countries, this would lead ultimately to the bank going out of businessits only purpose would be to collect the money it had already lent out. This is not a problem for regular banks because they can always recruit new customers, but the World Bank has a limited number of clients to which to lend money. Now what do you do? The Bank's solution was to lend still more. Robert McNamara, past chief of the Ford Motor Company and Secretary of Defense during the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson administrations, more than any one person, made the World Bank into what it is today. During his tenure from 1968 to 1981, the Bank increased lending from $953 million to $12.4 billion and increased staff from 1,574 to 5,201. The result was to leave many peripheral countries with a staggering debt burden. There were other problems as well.

The third source of the debt crisis was the oil boom of the early 1970s. Oil producers were making huge profits ('petrodollars'). The problem was that this money needed to be invested, particularly by the banks into which it went and from which depositors expected interest payments. But banks and other investment agents had a problem finding investments. One of their solutions was to lend even more money to peripheral countries. The source of the debt crisis is illustrated in Figure 3.2.

Thus, by the

late 1970s peripheral countries had borrowed huge sums of money and, with this

infusion, were doing generally well. But then financial policies in the wealthy

countries precipitated an economic collapse. With their own economies in recession

because of the increase in oil prices in the 1970s, core governments reacted by

raising interest rates. Countries such as

TABLE 3.2 External Debt of Selected Countries, 1980,1994, and 1998

|

|

Total External Debt |

External Dept |

as |

|||

|

|

|

(millions |

|

|

% of GNP |

|

|

Country |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

From World Development Report 1996:220-221; World Development Report 1999/2000: https://www. worldbank. org/wdr/2000/.

they could no longer pay back what they owed. Many couldn't even pay back the interest on the loans. Furthermore, an economic recession in the core nations decreased the demand for whatever commodities peripheral countries had for sale, further undermining their economies.

This all

sounds largely like an economic problem that would have little effect on people such as

you or me, or on a peasant fanner in

This debt has not only created problems for the debtor countries; it has created a major problem for lending institutions and investors. There is an old joke that says that when an individual can't pay his or her bank debts, he or she is in trouble, but when a big borrower, such as a corporation or country, can't repay its debts, the bank is in trouble.

This, in brief, was the dilemma posed by the global debt crisis for private lending institutions and the World Bank.

The World Bank and the IMF responded to the debt crisis by trying to reschedule the repayment of debts or extending short-term loans to debtor countries to help them meet the financial crises. However, to qualify for a rescheduling of a debt or loan payment a government had to agree to alter its fiscal policies to improve its balance-of-payments problems; that is, it had to try to take in more money and spend less. But how do you do that? There are various ways, all creating, in one way or another, serious problems. For example, countries had to promise to manage tax collecting better, sell government property, increase revenues by increasing exports, reduce government spending on social programs such as welfare, health, and education, promise to refrain from printing more money, and take steps to devalue their currency, thus making their goods cheaper for consumers in other countries but making them more expensive for their own citizens.

While these measures are rarely popular with their citizens, governments rarely refuse IMF requests to implement them because not only might they not receive a short-term loan, but agencies such as the World Bank and private capital controllers such as banks and foundations would also then refuse to make funds available. There is pressure on the World Bank and IMF to forgive or reduce debt, and forty-one of the poorest countries in the world have been targeted for debt relief of some sort (see Jubilee 2000). But for most countries, the interest alone on their debts dictates economic, environmental, and social policies that are devastating.

First, debt

means that countries must do whatever they can to reduce government expenses and

increase revenue or attract foreign investment. Reducing government expenses

means cutting essential health, education, and social programs. In

The effects on environmental

resources are equally devastating. To increase revenues, countries must export goods and resources. Since most indebted

countries, particularly those in sub-Saharan

Finally there is the question, where did all the money that was lent to peripheral countries go? Since 'capital flight'money leaving the peripheryincreased dramatically during the period of rising debt, the prevailing view is that loans were siphoned off

by the elites in the periphery

and invested back in the core. For example, while the IMF and other

financial institutions were lending billions to restore the Russian economy

after the fall of communism, $140 billion (

The Power of Capital Controllers

One of the enduring tensions in the culture of capitalism is the separation between political power and economic power; in a democracy, people grant the government power to act on their behalf. However, in capitalism, there are, in addition to elected leaders, capital controllers, individuals or groups who control economic resources that everyone depends on but who are accountable to virtually no one, except perhaps a few investors or stockholders. Their goals often conflict with state goals. As a merchant, industrialist, or investor your goals are simple: you want to attain the highest possible profit on your investment, you want to be certain your right to private property is protected, and you want to keep your financial risks to a minimum. As Jeffrey A. Winters (1996:x) suggested, if capital controllers, who are unelected, unappointed, and unaccountable, were all to wear yellow suits and meet weekly in huge halls to decide where, when, and how much of their capital (money) to invest, there would be little mystery in their power. But, of course, they don't. Collectively they make private decisions on where, when, and how to distribute their investments. Furthermore, under this system of private property, capital controllers are free to do whatever they wish with their capital: they can invest it, they can sit on it, or they can destroy it. States are virtually helpless to insist that private capital be used for anything other than what capital controllers want to do with it.

The anonymity of investors and the hidden power they hold (or that is hidden from us) present problems for political leaders: while the actions of capital controllers can greatly influence our lives, it is political leaders that we often hold responsible for the rise and fall of a country's financial fortunes. When unemployment increases, when prices rise, when taxes are raised or important services discontinued or decreased, we can fire our governmental representatives at the next election. However, we do not have the power to 'fire' the board of General Motors or the investment counselors at Smith, Barney's or Chase Manhattan.

Though investors may not consciously coordinate their actions, their choices have enormous consequences for societies and state leaders. The reasons for this are obvious. States depend on revenue for their operation and maintenance. This revenue can come from various sources, including income taxes, corporate taxes, tariffs on imported goods, revenue from state-run enterprises (e.g., oil revenue), charges for state services (e.g., tolls), foreign aid, and credit, loans, or grants from abroad. In the case of peripheral countries, much of this money comes from international lending agencies. But money from international lending agencies represents only a small percentage of the money that flows