| CATEGORII DOCUMENTE |

| Bulgara | Ceha slovaca | Croata | Engleza | Estona | Finlandeza | Franceza |

| Germana | Italiana | Letona | Lituaniana | Maghiara | Olandeza | Poloneza |

| Sarba | Slovena | Spaniola | Suedeza | Turca | Ucraineana |

The Nation-State in the Culture of Capitalism

The mutual relationship of modern culture and state is something quite new, and springs, inevitably, from the requirements of a modem economy.

Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism

Among the primary goals of the modern, post-Enlightenment state are assimilation, homogenization, and conformity within a fairly narrow ethnic and political range, as well as the creation of societal agreement about the kinds of people there are and the kinds there ought to be. The ideal state is one in which the illusion of a single nation-state is created and maintained and in which resistance is managed so that profound social upheaval, separatist activity, revolution, and coups d'etat are unthinkable for most people most of the time.

Carole Nagengast, Violence, Terror, and the Crisis of the State

Imagine an alien from another planet who lands on Earth after a nuclear holocaust has destroyed all life but has left undamaged terrestrial libraries and archives. After consulting the archives, suggested Eric Hobsbawm, our observer would undoubtedly conclude that the last two centuries of human history are incomprehensible without an understanding of the term nation and the phenomenon of nationalism.

The nation-state, along with the consumer, laborer, and capitalist, are, we suggest, the essential elements of the culture of capitalism. It is the nation-state, as Eric Wolf (1982:100) suggested, that guarantees the ownership of private property and the means of production and provides support for disciplining the work force. The state also has to provide and maintain the economic infrastructuretransportation, communication, judicial systems, education, and so onrequired by capitalist production. The nation-state must regulate conflicts between competing capitalists at home and abroad, by diplomacy if possible, by war if necessary. The state plays an essential role in creating conditions that inhibit or promote consumption, controls legislation that may force people off the land to seek wage labor, legislates to regulate or deregulate corporations, controls the money supply, initiates economic, political, and social policies to attract capital, and controls the legitimate use of force. Without the nation-state to regulate commerce and trade within its

own borders, there could be no effective global economic integration. But how did the nation-state come to exist, and how does it succeed in binding together often disparate and conflicting groups?

Virtually all people in the world consider themselves members of a nation-state. The notion of a person without a nation, said Ernest Gellner (1983:6), strains the imagination; a person must have a nationality as he or she must have a nose and two ears. We are Americans, Mexicans, Bolivians, Italians, Indonesians, Kenyans, or members of any of close to two hundred states that currently exist. We generally consider our country, whichever it is, as imbued with tradition, a history that glorifies its founding and makes heroes of those thought to have been instrumental in its creation. Symbols of the nation flags, buildings, monumentstake on the aura of sacred relics.

The attainment of 'nationhood' had become by the middle of the twentieth century a sign of progress and modernity. To be less than a nationa tribe, an ethnic group, a regional blocwas a sign of backwardness. Yet fewer than one-third of the almost two-hundred states in the world are more than thirty years old; only a few go back to the nineteenth century; and virtually none go back in their present form beyond that. Before that time people identified themselves as members of kinship groups, villages, cities, or, perhaps, regions, but almost never as members of nations. For the most part, the agents of the state were resented, feared, or hated because of their demands for tribute, taxes, or army conscripts.

States

existed, of course, and have existed for five to seven thousand years. But the

idea of the nation-state, of a people sharing some bounded territory, united by

a common culture or

tradition, common language, or common race, is a product of nineteenth century

The question of killing is important, because today most killing and violence is either sanctioned by or carried out by the state. This should not surprise us: most definitions of the state, following Max Weber's (1947:124-135), revolve around its claim to a monopoly on the instruments of death and violence. 'Stateness,' as Elman Service (1975) put it, can be identified simply by locating 'the power of force in addition to the power of authority.' Killing by other than the state, as Morton Fried (1967) noted, will draw the punitive action of organized state force.

The use of force, however, is not the only characteristic anthropologists emphasize in identifying the state; social stratificationthe division of societies into groups with differing access to wealth and other resourcesis also paramount. Yet even here the state is seen as serving as an instrument of control to maintain the privileges of the ruling group, and this, too, generally requires a monopoly on the use of force (see Cohen and Service 1978; Lewellen 1983).

Thus to complete our description of the key features of the culture of capitalism we need to examine the origin and history of the state and its successor, the nation-state.

The Origin and History of the State

The Evolution of the State

States represent a form of social contract in which the public ostensibly has consented to assign to the state a monopoly on force and agreed that only it can constrain and coerce people (Nagengast 1994:1116). Philosophers and political thinkers have long been fascinated by the question of why the state developed. Seventeenth-century philosopher Thomas Hobbes assumed the state existed to maintain order, that without the state life would be, in Hobbes's famous description, 'nasty, brutish, and short.' However, anthropologists have long recognized that some societies do very well without anything approaching state organization; in fact 'tribes without rulers,' as they were called, represented until seven to eight thousand years ago the only form of political organization in the world. Government in these societies was relatively simple. There might be a chief or village leader, but their powers were limited. In gathering and hunting societies most decisions were probably made by consensus. Village or clan chiefs may have had more authority than others, but even they led more by example than by force. Power, the ability to control people, was generally diffused among many individuals or groups.

The state as a

stratified society presided over by a ruling elite with the power to draw from

and demand agricultural surpluses likely developed in the flood plains between the

Tigris and Euphrates in what is now

Anthropologists have long been concerned with the idea of the origin of the state (see Lewellen 1992). Why didn't human aggregates remain organized into small units or into villages or towns of 500-2,000 persons? What made the development of densely settled cities necessary? Why, after hundreds of thousands of years, did ruling elites with control of armed force emerge to dominate the human landscape?

One theory is that as the population increased and food production became more complex, a class of specialists emerged and created a stratified society. Who comprised this class or why they emerged is an open question. Karl Wittfogel (1957), in his 'hydraulic theory' of state development, proposed that neolithic farmers in the area where states developed were dependent on flooding rivers, such as the Tigris, the Nile, and the Yellow Rivers, to water their fields and deposit new soil. But this happened only once each year, so to support an expanding population farmers began to build dikes, canals, and reservoirs to control water flow. As these irrigation systems became more complex, groups of specialists emerged to plan and direct these activities, and this group developed into an administrative elite that ruled over despotic, centralized states.

Others propose that an increase in population, especially where populations cannot easily disperse, requires more formal means of government and control and will lead to greater social stratification and inequality. These theories of state development emphasize the integrative function of the state and suggest that it evolved to maintain order and direct societal growth and development.

However, another framework emerges from the work of Marx and Engels. In this framework early societies were thought to be communistic, with resources shared equally among members and little or no notion of private property. However, technological development permitted production of a surplus of goods, which could be expropriated and used by some persons to elevate their control or power in society. Asserting control permitted this elite to form an entrepreneurial class. To maintain their wealth and authority, they created structures of force.

The major criticism of this framework from anthropologists is that there is little evidence of this kind of entrepreneurial activity in prehistoric societies; moreover, it is difficult to apply notions such as 'communism' and 'capitalism' to early societies. However, Morton Fried (1967) proposed that differential access to wealth and resources creates stratification, and once stratification emerges it creates internal conflict that will lead to either disintegration of the group or to the elite imposing their authority by force.

Yet another view proposes that external conflict is the motivation for state development: Once a group united under a strong central authority develops, it could easily conquer smaller, less centralized groups and take captives, land, or property. Following this line of reasoning, if smaller groups were to protect themselves from predator states they too had to organize, the result being the emergence of competing states with the more powerful ones conquering the weaker ones and enlarging their boundaries. Robert Car-neiro (1978) reasoned that war has served to promote consolidation of isolated, politically autonomous villages into chiefdoms of united villages and into states. At first war pits village against village, resulting in chiefdoms; then it pits chiefdom against chiefdom, resulting in states; and then it pits state against state, creating yet larger political units.

It should be clear that these theories are not mutually exclusive; the emergence of states may be a result of any one or a combination of factors. Thus, other theorists, such as Marvin Harris (1971) and Kent Flannery (1972, 1973), propose that the evolution of the state required the interaction of various factors such as control of birth rates, nature of food resources, and the environment.

Regardless of

why the state emerged as a human institution, it is clear that by 1400 the world was very much divided

into states and empires ruled by groups of elites who maintained their

positions through the use of force. But the states of prehistoric times the

city-states of ancient Greece, the Roman Empire, the Chinese dynastieswere

very different from the modern

nation-state. It is doubtful that subjects of the Ming Dynasty or

The History and Function of the Nation-State

The state as it exists today is obviously very different from the state that evolved seven thousand years ago or the state as it existed in the years 1500 or 1800. We have gone from being states to being nations or nation-states. The differences are important. A state is a

political entity with identifiable components. If someone asked citizens of the United States to identify a constituent of the 'state' they could point to federal buildings (e.g., the Congressional Office Building, the White House, federal courthouse), name federal bureaucracies (e.g., Congress, the Internal Revenue Service, the Department of Agriculture); they could list the things that the state requires of themto pay taxes, register for social security, obtain citizenship, vote. However, if someone asked them what constituted the 'nation,' what, other than the flag, could they point to? Other than being 'patriotic,' what could they say is required of them by the 'nation'? The American nation is a far more abstract concept than the American state; a nation, as Benedict Anderson (1991:5-6) put it, is 'an imagined political community.' Yet in the last two hundred years, states have evolved to nations or nation-states. But why did a new form of political entity develop, and what function did it perform?

The modern state, suggested Fernand Braudel (1982:515-516), has three tasks: to secure obedience and gain a monopoly on force with legitimate violence; to exert control over economic life to ensure the orderly circulation of goods and to take for itself a share of the national income to pay for its own expenditure, luxury, administration, or wars; and to participate in spiritual or religious life and derive additional strength by using religious values or establishing a state religion. We will examine later the use of violence by the state and the use of religious values. Let's first examine the state control of economic life.

The state has probably always been involved in its subjects' economic life in one way or another. The ancient state existed partly to protect the privileges of the elites by ensuring production of resources, offering protection from other elites, and extracting surplus wealth from a largely peasant population. Traders supplied wealth to the elite in the form of taxes, tributes, and fees required to do business. The state also performed some functions for the traderit might mint coins and produce paper money, establish standards for weights and measures, protect the movement of merchants and goods, purchase goods, and create and maintain marketplaces where merchants could sell their products. But the ancient states probably did little actively to encourage trade, and in many ways they may have inhibited it. For example, they may have taxed the merchant to an extent that making a profit became difficult. The elite may have limited the goods that merchants could trade or limit the market for goods, for example by claiming exclusive rights to wear certain kinds of clothes or furs, hunt certain animals, eat certain foods, and inhabit certain sites.

In sixteenth-

and seventeenth-century Europe and

The state was also involved in the consumption of goods, either by purchasing goods or, again, using its military or bargaining power to open up foreign markets to its merchants. One of the most lucrative sources of manufacturers' profits was (and still is) the sale to governments of weapons and other goods and services (food, clothing, and transportation) necessary to maintain the military and other government services. While

ostensibly the military existed in core countries to protect the state against foreign invaders, it was far more often used to create and maintain colonies necessary for the success of domestic manufacture and trade and to maintain domestic order. Finally, the state organized and directed financial institutions, such as banks, that ensured the ready availability of capital.

The nation-state, said Immanuel Wallerstein (1989:170), became the major building block of the global economy. To be part of the interstate system required that political entities transform themselves into states that followed the rules of the interstate system. This system required for its operation an integrated division of labor, along with guarantees regarding the flow of money, goods, and persons. States were free to impose constraints on these flows but only within a set of rules enforced collectively by member states or, as it usually worked out, a few dominant states.

At the

beginning of the nineteenth century, the new capitalist state faced two problems. The

first was political. With the downfall of the doctrine of the divine right of

kings and the absolute state, political leaders faced a crisis of political

legitimacy. On what basis could they claim control of the state apparatus that had become so

critical for the emergence and success of

the 'national economy ' ? A second and related problem was economic:

How could the state promote the economic integration of all those within its

borders? While the English state could claim control over

Thus the degree of economic

integration of regions was weak or nonexistent. Not only did people speak different languages, they used different

currencies, had different standards and measures, and were downright hostile to

state officials. Wages and prices varied from area to area and

standardized vocational training was virtually nonexistent. Furthermore, tastes in commodities differed;

things manufactured or produced in one area might not appeal to people in other areas. Thus local economies existed

either side-by-side with or

independent of the so-called national economy. While countries such as

There was, however, a single

solution to both the political and the economic problem: to turn states into

nationsgroups of people who shared a common culture, language, and heritage and somehow belonged together

(or thought they did), worked together,

and shopped together. This was not easy to accomplish, since virtually all of

the major European states in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

were hodgepodges of languages, cultures,

and religions. When Garibaldi united a group of provinces into what was to become

If members of a state would see themselves as sharing a common culturea common heritage, language, and destinynot only could state leaders claim to represent the 'people,' whoever they might be, but the people could be more easily integrated into the national economy. They would, ideally, accept the same wages, speak the same language, use the same currency, have similar skills, and similar economic expectations, and, even better, demand the same goods. The question is, how do you go about constructing a nation?

Constructing the Nation-State

It has been argued by some, especially ardent nationalists of various persuasions, that nation-states are expressions of preexisting cultural, linguistic, religious, ethnic, or historical features shared by people who make up or would make up a state. For many of the nineteenth-century German writers who were instrumental in creating the idea of the nation-stateJohann Gottfried von Herder, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, and Wilhelm Freiherr von Humboldtnations were expressions of shared language, tradition, race, and state. Thus today we see some of the citizens of Quebec claiming that their cultural heritage and language differentiates them from the rest of Canada and entitles them to nationhood; Kurds aspiring to their own state on the basis of cultural unity; Bosnian Serbs demanding their own state on the basis of their ethnic purity; and Sikhs demanding their own state based on their mode of worship.

However, the more generally held view, certainly among scholars, is that nation-states are constructed through invention and social engineering. Traditions, suggested Eric Hobsbawm, must be invented. People must be convinced that they share or must be forced to share certain features such as language, religion, ethnic group membership, or a common historical heritage, whether or not they really do. As Hobsbawm and Ranger (1983:1) put it,

'Invented tradition' is taken to mean a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behavior by repetition, which automatically implies continuity with the past. In fact, were it possible, they normally attempt to establish continuity with a suitable historic past.

Creating the Other

An understanding of how the nation-state and, by

extension, people's national identities are constructed is critical to understanding

nationalism and ethnicity. Let's begin by examining some of the ways

Sir David Wilkie's painting Chelsea Pensioners Reading the Gazette of the Battle of Waterloo represents the power of the nation-state to transcend boundaries of age, gender, class, ethnicity, and occupation.

people from all over

Outsiders, however, can be used in more symbolic ways to build national unity. For example, Colley suggested that the making of the British nation from its culturally and linguistically diverse populations would have been impossible without a shared religion, that British Protestantism allowed the English, Scots, and Welsh to overcome their cultural divergence to identify themselves as a nation. However, that would not have been so effective had their religion not also distinguished them from their arch rival, Catholic France.

Furthermore,

the founding of a colonial empire created additional Others from whom members of the British nation

could distinguish themselves. Britons thought the establishment of an empire proved

peoples fed Britons' belief

about their superiority. They could favorably compare their treatment of women,

their wealth, and their power. The building of a global empire corroborated

not only

Thus one of the most effective ways to construct a nation is to create some Other against whom members of the nation-state can distinguish themselves. That Other needn't be a country; it may be a category of persons constructed out of largely arbitrary criteria such as racial characteristics or religion. Thus a group may insist that only people of a particular skin color or religion or who speak a particular language can be members of their nation. War, religion, and the creation of colonies full of subjugated peoples provided for Britons a sense of their collective identity as a people, allowing them to overcome their own significant differences in language, culture, and economic status. Of course people must find it in their own self-interest as well to proclaim their identity as members of a nation-state. As Colley pointed out, men and women became British patriots to obtain jobs in the state or to advertise their standing in the community. Some believed that British imperialism would benefit them economically or that a French victory would harm them. For some, being an active patriot served to provide them full citizenship and a voice in the running of the state.

Yet the creation of hated or feared Others through such means as war, religion, and empire building is probably not in itself sufficient to build loyalty and devotion to a nation. If it were, the nation-state would likely have emerged well before it did. Constructing a nation-state also requires a national, bureaucratic infrastructure that serves in various ways to unite people.

Language, Bureaucracy, and Education

Eugen Weber, in his book Peasants

into Frenchmen (1976), provided a classic account of nation

building; he documented how peoples in France were administratively molded into

a

nation by bringing the French language to the countryside, by increasing the

ease of travel, by increasing access to national media, through military

training, and, most important, through a national educational system. Weber

(1976:486) compared the transformation of peasants into citizens of a French

nation-state to the process of colonization and acculturation: unassimilated

masses had to be integrated into a dominant culture. The process, he

suggested, was akin to colonization, except it took place within the borders of

the country rather

than overseas. What kind of transformation of national identity did take

place in

At the

beginning of the nineteenth century, even after the French Revolution, a significant

portion of rural

State officials saw linguistic

diversity as a threat not to administrative unity but to ideological unity, a shared notion of the

interests of the republic, a oneness. Linguistic and cultural diversity came to be seen as imperfection, something to be

remedied (Weber 1976:9). As a result, in the 1880s, at the insistence of

the government, the French language began to infiltrate the countryside, a

process more or less complete by 1914, although

even in 1906 English travelers in

With the homogenization of language

came the homogenization of culture. Local customs began to be replaced, dress

and food preferences became standardized. While many aspects of local culture began to disappear, some were adopted as

national symbols. The beret, worn only by Basques in 1920, became by

1930 a symbol of

|

|

|

Third graders

in |

Another sign of state integration and the decline of local traditions and values is the decay of popular feasts and rituals that celebrated the unity of local groups, and their replacement by private ceremonies and rituals along with a few national holidays. Communal celebrations such as Christmas, New Year, and Twelfth Night turned into family affairs. Where once they were public rituals, baptisms, first communions, and marriages became private ceremonies. Renewal ceremonies that glorified time (the season), work (harvest), or the community (through its patron saint) disappeared as the redistribution of

goods once done through ritual at these ceremonies was

now managed more efficiently (and more

stringently) by the state (Weber 1976:398). The replacement of local holidays and festivals with national holidays also allowed

these occasions to be turned into periods of massive consumption and gift giving, like Valentine's Day, Easter,

Mother's Day, and Christmas in the

National unity

in

Thus in the nineteenth century

people living within the boundaries of the French state gradually learned to be French. But how did this happen; how

were peasants turned into French citizens? As with

New roads were built, connecting people to others to whom they had never been connected; the growth of the railroads further increased mobility and contact between people of different regions. The railroads helped to homogenize tastes. While we now associate the French with wine drinking, wine was not common in the countryside in the first half of the nineteenth century, becoming more available only with the railroads. The roads and railroads brought peasants into a national market; it allowed them to grow and sell crops they couldn't sell before and to stop growing those they could purchase more cheaplybringing ruin to some local enterprises no longer protected by isolation. Fashions from the cities began to penetrate the countryside. And the roads and railroads set people on the move. If people migrated in the early part of the nineteenth century to find work, they almost always returned. This was no longer true by the end of the century.

As more people spoke French and

became literate, they gained access to newspapers

and journals, which in turn increased knowledge of national affairs and

interests, demonstrating that events at the national level affected

their lives. Military service increased identification with the state. Prior

to the 1890s there was little sense of national identity in being a soldier;

soldiers were either feared or thought to bring bad habits to their communities. Local men who joined the army

were forced to conform when they returned to their villages lest their

newly learned habits affect others. Many returned not even having learned to speak French. But the war with

As important

as all these agents of nation building were in

At the beginning of the century

educational conditions were abysmal in

It was clear to state officials that education was necessary as a 'guarantee of order and social stability' (Weber 1976:331). 'To instruct the people,' one said, 'is to condition them to understand and appreciate the beneficence of the government' (Weber 1976:331). Clearly there was an explicit link in the minds of state officials between education, nation building, national identity, and economic expansion. Following is a passage from a first-year civics textbook that helped students in 'appreciating their condition.'

Society (summary): (1) French

society is ruled by just laws, because it is a democratic society. (2) All the

French are equal in their rights: but there are inequalities between us that stem from

nature or from wealth. (3) These inequalities cannot disappear. (4) Man works to become

rich; if he lacked this hope, work would cease and

Schooling was to be the great agent of nationalism. As one teacher said in 1861, it would teach national and patriotic sentiments, explain the benefits of the state and why taxes and military service were necessary, and illustrate for students their true interest in the fatherland. In 1881, another wrote that future instructors must be taught that 'their first duty is to make [their charges] love and understand the fatherland.' By the 1890s officials considered the school 'an instrument of unity,' an 'answer to dangerous centrifugal tendencies,' and the 'keystone of national defense' (Weber 1976:332-333).

The best instrument of indoctrination, said school officials, was history, which, when properly taught, 'is the only means of maintaining patriotism in the generation we are bringing up.' In 1897 candidates for the baccalauret moderne were asked to define the purpose of history in education; 80 percent replied essentially that it was to exalt patriotism (Weber 1976:333).

Before 1870 few schools had maps of

Ernest Gellner (1983:34) drew the connection between nation building, education, and economic integration even more tightly. According to Gellner, work in industrial society no longer means working with things, rather it involves working with meanings, exchanging communications with other people, or manipulating the controls of machines,

controls that need to be understood. It is easy to understand the workings of a shovel or a plow; it is another thing to understand the complex process through which a button or control activates a machine. As a consequence, a modern capitalistic economy requires a mobile division of labor and precise communication between strangers. It requires universal literacy, a high level of numerical, technical, and general sophistication, mobility where members must be prepared to shift from area to area and from task to task, an ability to communicate with people they don't know in a context-dependent form of communication, in a common, standardized language. To attain the standard of literacy and technical competence needed to be employable, people must be trained, not by members of their own local group but by specialists. This training could be provided only by something like a 'national' education system. Gellner (1983:34) went so far as to suggest that education became the ultimate instrument of state power, that the professor and the classroom came to replace the executioner and the guillotine as the enforcer of national sovereignty, and that a monopoly on legitimate education became more important than the monopoly on legitimate violence to build a common national identity and to provide the training necessary for the full integration of national economies.

Violence and Genocide

While creating a feared or hated

Other, a national bureaucracy, and an educational system are essential in constructing the

nation-state, violence remains one of the main tools of nation building. In fact there is a view, shared in anthropology by

Pierre van den Berghe (1992), Leo

Kuper (1990), Carole Nagengast (1994), and others, that the modern nation-state is essentially an agent of genocide and

ethnocide (the suppression and destruction of minority cultures). Given the glorification of the nation-state as a

vehicle of modernization, unity, and

economic development, this seems a harsh accusation. Yet there exists ample evidence that one of the ways states have sought to

create nations is to eliminate or terrorize into submission those within its

borders who refuse to assimilate or who demand recognition of their status as a distinct ethnic or

national group. In the

Between 1975

and 1979, in one of the worst cases of state killing in the twentieth century, the

government of Cambodia, the Khmer Rouge, systematically killed as many as two million

of its seven million citizens. These killings were carried out in the name of a

program

to create a society without cities, money, families, markets, or commodity-money

relations.

Millions were disembowelled, had nails driven into the backs of their heads, or

were

beaten to death with hoes. This program involved destroying what the leaders

saw as the enemy classesimperialists (e.g., ethnic Vietnamese, ethnic Chinese,

Muslim Chams), feudalists (the leaders of the old regime, Buddhist

monks, intellectuals), and comprador capitalists (ethnic Chinese). The goal was

as much nationalistic as it was socialisticto return

they deemed didn't belong (Kuper 1990). But the killing of its citizens by the Khmer Rouge, while reaching an intensity matched by few states, was hardly an exception. As Carole Nagengast (1994:119-120) wrote:

The numbers of people worldwide subjected to the violence of their own states are staggering. More than a quarter of a million Kurds and Turks in Turkey have been beaten or tortured by the military, police, and prison guards since 1980; tens of thousands of indigenous people in Peru and Guatemala, street children in Brazil and Guatemala, Palestinians in Kuwait, Kurds in Iraq, and Muslim women and girls in Bosnia have been similarly treated. Mutilated bodies turn up somewhere everyday. Some 6000 people in dozens of countries were legally shot, hung, electrocuted, gassed, or stoned to death by their respective states between 1985 and 1992 for political misdeeds: criticism of the state, membership in banned political parties or groups, or for adherence to the 'wrong' religion; for moral deeds: adultery, prostitution, homosexuality, sodomy, or alcohol or drug use; for economic offenses: burglary, embezzling, and corruption; and for violent crimes: rape, assault, and murder.

R. J. Rummel (1994), in a series of books on state killing, documented the carnage committed by states against their own citizens: 61 million Russians from 1917 to 1987; 20 million Germans from 1933 to 1945; 35 million Chinese killed by the Chinese communist government from 1923 to 1949 and 10 million killed by the Chinese nationalists; almost 2 million Turks from 1909 to 1918; and almost 1.5 million Mexicans from 1900 to 1920. In total, Rummel (1994:9) said, almost 170 million men, women, and children from 1900 to 1987

have been shot, beaten, tortured, knifed, burned, starved, frozen, crushed, or worked to death; buried alive, drowned, hung, bombed, or killed in any other of the myriad ways governments have inflicted death on unarmed, helpless citizens and foreigners. The dead could conceivably be nearly 360 million people. It is as though our species has been devastated by a modern Black Plague. And indeed it has, but a plague of Power not germs.

Rummel attributed state killing to power and its abuses, claiming it is largely totalitarian regimes that resort to democide, genocide, or ethnocide. Democracies also kill, as evidenced in the twentieth century by indiscriminate bombings of enemy civilians in war, the large-scale massacre of Filipinos during U.S. colonization of the Philippines at the turn of the century, deaths in British concentration camps during the Boer War in South Africa, civilian deaths in Germany as a result of the Allied blockade, the rape and murder of helpless Chinese in and around Peking in 1900, atrocities committed by Americans in Vietnam, the murder of helpless Algerians by the French during the Algerian War, and the deaths of German prisoners of war in French and U.S. prisoner of war camps after World War II. But Rummel said even these prove his point about power, for virtually all of these cases were committed in secret behind a trail of lies and deceit by agencies and power holders who were given the authority to operate autonomously and shielded from the press. Even attacks on German and Vietnamese cities were presented as attacks on military targets. He concluded that as we move from democratic through authoritarian and to totalitarian governments, the degree of state killing increases dramatically (Rummel 1994:17).

Pierre van den Berghe (1992:191) attributed state killing not to the misuse of authority but to nation building itself. Taking what he called a frankly anarchist position, he said

the process euphemistically described as nation-building is, in fact, mostly nation-killing; that the vast majority of so-called 'nation-states' are nothing of the sort; and that modern nationalism is a blueprint for ethnocide at best, genocide at worst.

Van den Burghe said that the nation-state myth has been allowed to persist because international bodies such as the United Nations insist that internal killing is a state matter, a 'gentlemen's agreement' between member states not to protest the butchering of their own citizens. Also, scholars perpetrate the myth with the use of nation-state designation. The result is to legitimize genocide in the interests of building nation-states that function to further economic and political integration.

Carole Nagengast (1994:122) proposed that state-sponsored violence serves to aid in the construction and maintenance of the nation-state. She examined not only state killing but also the institutionalization of torture, rape, and homosexual assault. The purpose of this state-sponsored violence is not to inflict pain but to create what Nagengast called 'punishable categories of people,' to create and maintain boundaries and legitimate or de-legitimate specific groups. State violence against its own citizens, she suggested, is a way to create an Other, an ambiguous underclass that consists on the one hand of subhuman brutes and on the other hand of superhuman individuals capable of undermining the accepted order of society. Arrest and torture serves to stigmatize people and to mark them as people who no one wants to be. Arrest and torture become, in effect, a way of symbolically marking, disciplining, and stigmatizing those categories of people whose existence or demands threaten the idea, power, and legitimacy of the nation-state. Furthermore, since the torture and violence are committed only against 'terrorists,' 'communists,' or 'separatists,' it becomes legitimate. 'We only beat bad people,' said a Turkish prison official in 1984. 'They are no good, they are worthless bums, they are subversives who think that communism will relieve them of the necessity of working.' He revealed with apparent pride that he had 'given orders that all prisoners should be struck with a truncheon below the waist on the rude parts, and warned not to come to prison again.' 'My aim,' he said, 'is to ensure discipline. That's not torture, for it is only the lazy, the idle, the vagabonds, the communists, the murderers who come to prison' (cited Nagengast 1994:121).

Terrorist acts are often depicted as being extra-legal; that is, committed by persons outside state control. Yet there is considerable evidence that most terror is applied by states to integrate or control a reluctant citizenry. As Jeffery Sluka (2000:1) puts it:

if terrorism means political intimidation by violence or its threat, and if we allow the definition to include violence by states and agents of states, then we find that the major form of terrorism in the world today is practiced by states and their agents and allies, and that quantitatively, anti-state terrorism pales into relative insignificance in comparison to it.

Death squads operate outside the law but with the tacit approval of the state. Thus their actions carry out state goals of eliminating dissidents without due process of law but are enough removed from official state agencies to allow the state 'plausible denial.'

Rarely are members of death squads punished, and many are also members of official state agencies such as the police, militia, or army.

Targets of death squads are often

portrayed by the state as 'terrorists' or subversives but tend to be

anyone that challenges the status quo. These include people who organize unions, offer Bible classes, propose land

reforms, or advocate tax increases on the rich. They include clergy,

labor organizers, human rights activists, social workers, journalists, and so on. Victims include women,

children, the elderly, and relatives of activists. More recently,

particularly in

Few countries

are immune to the operation of state-sanctioned death squads. In the

One of the

most recent case of large scale global paramilitary violence occurred in September of 1999 after 78.5% of

the people of East Timor had voted for independence from

Core countries play a major role in supporting violent regimes in the periphery by either training officers or offering direct military aid. Virtually all this military support is used, not to defend against foreign invasion, but to suppress political dissent or unionization or to discipline a resistant citizenry. And the financial cost of maintaining militaries and supplying client states is high (see Table 4.1 on pp. 118-119).

Alexander George in his book Western State Terrorism concludes that

The plain and painful truth is that on any reasonable definition of terrorism, taken literally, the United States and its friends are the major supporters, sponsors, and perpetrators of terrorist incidents in the world todaymany, probably most, significant instances of terrorism are supported, if not organized, by the U.S., its partners, and their client states (George 1991:1-2)

The Future of the Nation-State

The nation-state as currently conceived is two to three hundred years old. But what is its future? Some suggest that nation-states are no longer viable or necessary and will disintegrate into smaller, more culturally homogeneous units. Others (see, e.g., Smith 1995) suggest that the nation-state is still the most sensible solution to problems of social and economic order.

There are, however, three developments that seem to threaten the integrity of nation-states: transnationalism, an increase in the number of people living and working in countries other than the one in which they hold citizenship; the growing power and influence of

'Many of these photographs are available on the Web. See for example: https://www.berea.edu/ENG/chesnutt/ history.html

TABLE 4.1 Military Expenditures, Arms Exports, and Imports by Country1997

|

|

Arms Expenditures |

|

Arms Exports |

|

|

Arms Imports |

|

|

|

|

|

$ in |

|

|

$ in |

|

|

$ in |

|

Rank |

Country |

Millions |

Rank |

Country |

Millions |

Rank |

Country |

Millions |

|

1 |

|

276300 |

1 |

|

31800 |

1 |

|

11600 |

|

2 |

|

74910 |

2 |

|

6600 |

2 |

|

9200 |

|

3 |

|

41730 |

3 |

|

5900 |

3 |

|

2600 |

|

4 |

|

41520 |

4 |

|

2300 |

4 |

|

2100 |

|

5 |

|

40840 |

5 |

|

1100 |

5 |

|

2000 |

|

6 |

|

35290 |

6 |

|

900 |

6 |

|

1600 |

|

7 |

|

32870 |

7 |

|

750 |

7 |

|

1600 |

|

8 |

|

22720 |

8 |

|

700 |

8 |

|

1600 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9 |

United Arab |

|

|

9 |

|

21150 |

9 |

|

550 |

|

Emirates |

1400 |

|

10 |

|

15020 |

10 |

|

525 |

10 |

|

1100 |

|

11 |

|

14150 |

11 |

|

500 |

11 |

|

1100 |

|

12 |

|

13060 |

12 |

|

500 |

12 |

|

950 |

|

13 |

|

10850 |

13 |

|

490 |

13 |

|

925 |

|

14 |

|

9335 |

14 |

|

370 |

14 |

|

850 |

|

15 |

|

8463 |

15 |

|

370 |

15 |

|

850 |

|

16 |

|

7800 |

16 |

|

120 |

16 |

|

750 |

|

17 |

|

7792 |

17 |

|

110 |

17 |

|

725 |

|

18 |

|

7670 |

18 |

|

90 |

18 |

|

625 |

|

19 |

|

6839 |

19 |

|

90 |

19 |

|

600 |

|

20 |

|

6000 |

20 |

|

90 |

20 |

|

500 |

|

21 |

|

5664 |

21 |

|

70 |

21 |

|

480 |

|

22 |

|

5598 |

22 |

|

70 |

22 |

|

460 |

|

23 |

|

5550 |

23 |

|

60 |

23 |

|

430 |

|

24 |

|

5533 |

24 |

|

50 |

24 |

|

430 |

|

25 |

|

4812 |

25 |

|

50 |

25 |

|

430 |

|

26 |

|

4726 |

26 |

|

40 |

26 |

|

410 |

|

|

|

|

27 |

United Arab |

|

|

|

|

|

27 |

|

4294 |

|

Emirates |

40 |

27 |

|

410 |

|

28 |

|

4285 |

28 |

|

30 |

28 |

|

400 |

|

29 |

|

3859 |

29 |

|

30 |

29 |

|

370 |

|

30 |

|

3701 |

30 |

|

30 |

30 |

|

310 |

|

31 |

|

3686 |

31 |

|

30 |

31 |

|

310 |

|

32 |

|

3456 |

32 |

|

30 |

32 |

|

310 |

|

33 |

|

3403 |

33 |

|

20 |

33 |

|

310 |

|

34 |

|

3387 |

34 |

|

|

34 |

|

280 |

|

35 |

|

3381 |

35 |

|

20 |

35 |

|

270 |

|

36 |

|

3380 |

36 |

|

20 |

36 |

|

260 |

|

37 |

|

NA |

37 |

|

20 |

37 |

|

250 |

|

38 |

|

3253 |

38 |

|

20 |

38 |

|

250 |

|

39 |

|

2864 |

39 |

|

20 |

39 |

|

240 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

TABLE 4.1 Continued

|

|

Arms Expenditures |

|

Arms Exports |

|

|

Arms Imports |

|

|

|

|

|

$in |

|

|

$ in |

|

|

$ in |

|

Rank |

Country |

Millions |

Rank |

Country |

Millions |

Rank |

Country |

Millions |

|

40 |

|

2804 |

40 |

|

10 |

40 |

|

200 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

41 |

|

|

|

41 |

|

2761 |

41 |

|

10 |

|

|

180 |

|

42 |

|

2389 |

42 |

|

10 |

42 |

|

180 |

|

43 |

|

NA |

43 |

|

10 |

43 |

|

170 |

|

44 |

|

2322 |

44 |

|

10 |

44 |

|

160 |

|

45 |

United Arab |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Emirates |

2306 |

45 |

|

10 |

45 |

|

160 |

|

46 |

|

2285 |

46 |

|

10 |

46 |

|

150 |

|

47 |

|

2176 |

47 |

|

5 |

47 |

|

140 |

|

48 |

|

2089 |

48 |

|

5 |

48 |

Kazakstan |

140 |

|

49 |

|

NA |

49 |

|

5 |

49 |

|

130 |

|

50 |

|

2001 |

50 |

|

5 |

50 |

|

130 |

From

transnational corporations; and the growth in the number, and possibly influence, of nongovernmental organizations. Let's complete our examination of the nation-state by reviewing each of these developments.

Transnationalism and Migration

Lenin (1976) made the point that imperialism transported surplus capital from developed to undeveloped areas of the world and, as a consequence, destroyed local economies, replacing peasant fanning and small-scale industry with wage labor. But the economies of underdeveloped areas are incapable of absorbing the labor it has created, and that labor is now spilling over into the core of the world capitalist economy. Currently 2 percent of the world's population100 million peoplelive and work in countries of which they are not citizens.

Massive labor

migration is not a new thing; in the last half of the nineteenth century and the first

decades of the twentieth, as we saw in Chapter 2, millions of people migrated in search of land and wage labor.

The migrations of the 1980s and 1990s, however, are different in at least two

respects. First, labor migrants are maintaining or attempting to maintain close

ties with their home countries, and home countries are also attempting to maintain those ties. Not only do Haitian migrants

to the

state. Second, migrants are no longer as welcome in host core countries as they were in the nineteenth century, when there was an abundance of land and a shortage of labor. These two differences have created a very different view of migrants in their home countries and in the core countries in which they seek to work.

Linda Basch, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Szanton Blanc (1994:7), in their book Nations Unbound, labeled the process where people's lives are stretched across national boundaries as transnationalism. They defined transnationalism as

The process by which immigrants forge and sustain multi-stranded social relations that link together their societies of origin and settlement. We call these processes transnationalism to emphasize that many immigrants today build social fields that cross geographic, cultural, and political borders.

Transnationalism, they suggested, requires a reconceptualization of the nation-state; whereas it was once thought of as people sharing a common territory, it now must include citizens who are physically dispersed among other states but who remain socially, politically, culturally, and sometimes economically part of the nation-state of their ancestors (Basch et al., 1994:8).

They believe transnational migrants are a product of global capitalism, as the debt of peripheral countries has created massive unemployment. The unemployed are vulnerable in their own countries because they cannot find work and in the countries to which they migrate because they cannot compete on an equal basis and often are used as scapegoats. It is because of this economic and political vulnerability that migrants construct a transnational existence seeking work in core countries while at the same time maintaining ties with family at home (Basch et al., 1994:27). Consequently, transmigrants are engaged in the nation-building process of two or more nation-states, the state of their origin and the one to which they have migrated in search of work.

Haitian migrants to the

One motivation for maintaining of

ties arises from loyalty, sentiment, and emotional ties to

For the migrant's home country, migrants are valuable sources of foreign exchange. The home country's dilemma is how to take advantage of the money and goods that trans-

national migrants send home, while maintaining their

identity and loyalty. For example, to promote transnationalism in the

mid-1980s, Haitian leaders used Zionists as a model, Jews who were permanently part of

Viewed from the core, transnational migrants pose a different set of problems. The problem is that the often cheap labor supplied by the transnational migrant is desired, but the person who does the labor is not. The question is how to keep the borders open to cheap transnational labor while at the same time maintaining the boundaries of the nation-state? In the United States, for example, businesses want foreign labor, but the increase in the number of immigrants threatens some people's sense of their national identity; thus the increase in Spanish-speaking immigrants in the United States increased efforts to have Congress declare English the country's official language.

Michael Kearney (1991:58), examining the situation of the Mexican worker in the United States, suggested that immigration policy in core countries is largely directed to trying to separate the labor from the laborer: foreign labor is desired, but the person in which it is embodied is not. Consequently, the immigration policies of host countries must somehow separate labor from the person who supplies it, must 'disembody the labor from the migrant worker.'

One way to do

this is to pass punitive antimigrant legislation that allows migrants to work in the

Thus border

areas become contested zones, manifestations of the dilemma of exploiting the

laborer while denying the rights of the individual.

The differences in wealth between

the periphery and the core, the need of citizens of peripheral countries to

find jobs wherever they are, and the desire in capitalist economies to seek the cheapest labor combine to create

a dynamic that increases the number of transnational migrants working in

core countries and threatens the boundaries between nation-states.

Will Corporations Rule the World?

Some see yet another entity as a threat to the power of the nation-statethe transnational corporation. In many ways this institution seems a natural development in a process of economic integration that began centuries ago. One of the major dynamics for the development of the nation-state, as previously mentioned, is the need to integrate national economies. The growth of business and the creation of the consumer required standardized weights, measures, and currencies, common wages and prices, and a homogeneous consumer population such that a product produced in a given country would be desired by everyone in that country. The state was the main agency enforcing integration, through regulatory agencies, enforced wage and labor standards, and, perhaps most important, the development of state education and schools that would construct populations of Americans, French, English, Germans, Italians, and so on.

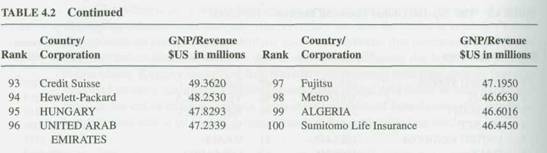

As states required economic integration within their borders, however, the modern global economy requires global, not just state, integration. The institution best equipped to perform the task of global integration, some argue, is the transnational corporation. David Korten (1995:12) suggested that these entities represent a shift of power away from governments, which are ideally responsible for the public good, toward a few corporations and financial institutions, in which are concentrated massive economic and political power and whose sole motive is the quest for short-term financial gain. The corporation, Korten argued, has evolved from an institution with limited power to one that some claim is the dominant governance institution of the world and which exceeds most governments in size and power (see Table 4.2). One consequence is that corporate interest, as opposed to human interests, defines the policy agendas of states and international agencies.

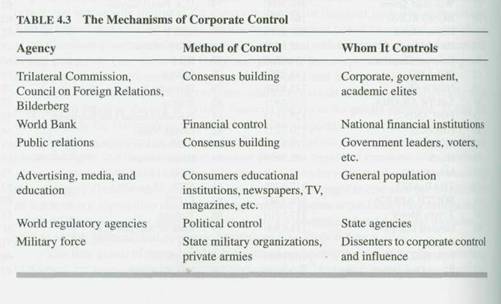

As we saw in Chapter 3, the corporate charter is a social invention that originally was supposed to promote the use of private financial resources for public purposes. It can be traced back to the sixteenth century. Since that time corporations have assumed enormous power and have advanced an ideology that Korten labeled corporate libertarianism, which places the rights and freedoms of corporations above the rights and freedoms of individuals. The question is, how have corporations managed to convince governments of the worth of this ideology? Perhaps more important, how have they managed to convince the public that its interests are identical to those of the corporation? Korten argued that corporations have advanced their interests by gaining control of various international and domestic agencies as well as social, political, and economic institutions (see Table 4.3 on p. 124).

The first group of agencies that function to advance corporate interests, according to Korten, are the Council on Foreign Relations, the Bilderberg (named for the Hotel de

|

|

123

123

Country GNP data from the World Economic Outlook 1999 Database (IMF) at https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2000/ 02/data/index.htm; corporate income data from Forbes' Global 500 at https://www.fortune.com/fortune/global500/

Bilderberg of Oosterbeek,

Carter administration. They describe themselves as a group of 325 distinguished citizens. Members have included heads of all the major corporations as well as American presidents (Carter, Bush, Clinton) and many who hold influential government posts. These institutions and others have brought together government, academic, and corporate leaders to create policy that directs the actions of governments and influential world agencies, such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the United Nations, toward full integration of the world's capitalist economy.

In addition to these 'informal' discussion groups, corporate libertarianism is evident in the working of the World Bank, which functions partly to control the financial links between corporations and borrowers. Thus the International Finance Corporation, one arm of the World Bank, functions to make government-guaranteed loans to private investors on projects deemed too risky for commercial banks.

Another way corporations sell their agenda is through lobbying groups and public relations efforts targeted to political leaders and the public. Until the 1970s this was done through straightforward lobbying groups, such as the Beer Institute and the National Coal Association. Today corporations try to mask their involvement by forming 'citizen' groups, such as the National Wetlands Coalition (with its logo of a duck flying over a swamp), sponsored by oil and gas drilling companies and real estate developers fighting for lessening of restrictions on the conversion of wetlands to drilling sites and shopping malls. Keep America Green, sponsored by the bottling industry, argues for antilitter campaigns rather than mandatory recycling legislation.

Protected by the free speech

provision of the First Amendment, corporations marshal huge public relations efforts on behalf of their agendas. In the

Finally, in the 1980s and 1990s corporations gained formal control over international regulatory agencies. The assumption of this control began with the Bretton Woods initiative and culminated with the World Trade Organization. The WTO has the power to override rules and legislation passed by countries and local governments if its three-person panel, in private, decides that the rules 'unfairly' inhibit free trade. Thus, the modern transnational corporation can use public policy forums, international financial agencies, public relations organizations, the media, schools, and world regulatory agencies to convince government leaders and the public of courses of action that ensure profit making and reduce the risk of financial failure. Furthermore, to the extent that individual lives are influenced by corporate ideology, we may also be witnessing the increase of the authoritarian governance systems common to corporations.

|

|

The powers exercised by corporations through government, through private and public institutions, and through public relations specialists can often result in the voting public supporting actions that may not be in their best interest.

Reprinted with the permission of John Jonik.

It would seem that the only agency

of control lacking in the corporation is armed force. Yet corporations have sometimes managed to co-opt the military of

nation-states to serve their own ends or even, on occasion, to organize and

equip their own private armies. Early

in their development, corporations made use of armies, national guards, and

sometimes even their own private military force to end strikes or

punish or repress urban and rural protest. Even today corporations often become

closely involved in state repression. In 1995 Shell Oil Corporation supplied

arms to the Nigerian government as it sought to repress the Ogoni peoples, who

were demanding that Shell cease polluting Ogoni lands. Shell earned worldwide

condemnation for its involvement and possible acquiescence in the execution of

Ogoni leader Ken Saro Wira. Oil companies such as Local 66 have lent direct or indirect support to the repressive

regime in

ernments, to keep or attract foreign corporate investment, systematically repress and make war on minorities whose demands lend an impression of government instability that state leaders fear will scare away foreign investors.

Yet, as powerful as corporations have become, it is difficult to see them operating without the nation-state. Some have argued that, in fact, the nation-state is, by and large, an extension of the corporation, creating conditions necessary for the maintenance of perpetual growth (see, e.g., Wallerstein 1997). Nation-states must adopt policies to promote 'competitiveness,' to promote the free movement of capital, and confine labor within national boundaries. Furthermore the nation-state must create and enforce rules that permit the various costs involved in doing business to be 'externalized' and passed on to the general public, marginalized persons, or to future generations.

Corporations rarely, if ever, pay

the full cost of production. And consumers never directly pay the real price of

things. For example, take the price of gasoline. A gallon of gasoline is currently selling in the

First, the

Then there are the environmental,

health, and social costs that are not reflected in the price we pay at the

pump. The

These are just samples of the hidden costs of gasoline; if we were to add to these the hidden costs of our dependence on the automobile, of course, these costs would skyrocket. Thus, without the nation-state to pass laws and regulations and to provide needed services for the maintenance of trade, the direct cost of virtually all the items that we buy, from candy bars (see Robbins 2000) to automobiles, would be many times higher than they are. And if we were to add up the hidden costs of all the items that define even a middle-class life style in the culture of capitalism, we would be able to appreciate the role of the nation-state in making that lifestyle economically feasible. Of course, these hidden prices need to be paid at some point by someone; consequently we must pay them in higher taxes or

health costs, or others must pay them in lower wages or health or environmental risks; otherwise the costs must be paid by future generations.

Nongovernmental Organizations

Another set of global organizations that some claim presents an alternative to the nation-state is the nongovernmental organization (NGO). These organizationsalso called the nonprofit sector, independent sector, volunteer sector, civic society, grassroots organizations (GROs), transnational social movement organizations, and nonstate actorsgenerally represent any organization, group, or institution that fulfills a public function but is not a part of the government of the territories in which it works. Nongovernmental organizations may be large transnational organizations, such as Amnesty International or the Red Cross, or small, local-level groups, such as a neighborhood group organized to provide day care. Generally it is the large international groups that some see as alternatives to nation-states.

There are various ways of conceptualizing the role of NGOs in relation to other political and economic bodies. Lester M. Salamon and Helmut K. Anheier (1996:129) suggested that NGOs represent a third sector in global governance, the other two being the state and the corporation (or 'market'). Marc Nerfin (1986) suggested that politically we can conceptualize NGOs using the metaphor of the prince, the merchant, and the people, with governmental power and the maintenance of public order the job of the prince, economic power and the production of goods and services the job of the merchant, and NGOs representing the citizen, the power of the people. In this framework, NGOs developed from citizen demands for accountability from the prince and merchant, competing with them for power and influence, and demanding that neglected groups (e.g., the poor, children) be heard (see Weiss and Gordenker 1996:19; Korten 1990:95ff).

The NGO as we

know it dates from the founding of the International Red Cross in

Why have NGOs

increased in importance? First, some suggest that the end of the Cold War made

it easier for NGOs to operate without being drawn into the conflict between the West

and the Communist Bloc. Second, revolutions in communication, particularly

through the Internet, have helped create new global communities and bonds

between like-minded

people across state boundaries. Third, there are increased resources and a growing professionalism in NGOs. In 1994, 10

percent of public development aid ($8 billion) was channeled through

NGOs, including 25 percent of

ployment. Fourth, there is the media's ability to inform more people about global problems. With this increased awareness, the public, particularly but not exclusively in core countries, demand that their governments take action. Finally, and perhaps most important, some people suggest that NGOs have developed as part of a larger, neoliberal economic and political agenda. Edwards and Hulme (1995:4), in Non-Governmental Organizations, maintained that the rise in importance of NGOs is neither an accident nor simply a response to local initiative or voluntary action. More important, they said, is the increasing support of NGOs from governments and official aid agencies acting in response to shifts in economic and political ideology.

Neoliberal economics assumes that markets and private initiative are the most efficient mechanisms for achieving economic growth and providing effective services. Governments, the theory assumes, should minimize their role in government because NGOs are more efficient in providing service. Thus NGOs are seen by nation-states themselves as the preferred way of delivering educational, welfare, and health services (Edwards and Hulme 1995:4). As a consequence, there is a good deal of evidence to suggest that NGOs are growing because of increased amounts of public funding. In recent years NGOs not dependent on state aid are the exception rather than the rule; furthermore, most of the aid has gone primarily to finance welfare services and development. Thus NGOs serve to replace, perhaps at a lower cost, the services in welfare, health, and education that peripheral countries are being forced to cut in exchange for World Bank loans, foreign investments, or loan restructuring.

There is plenty of evidence that the growth in size and number of NGOs is fed by increased governmental contributions along with greater contributions from multilateral developmental organizations such as the World Bank. On the one hand, these conditions have created additional monies for NGOs and GROs to develop; on the other hand, they risk becoming so dependent on governments that they have been co-opted and their independence threatened.

Regardless of the reasons for their increase there is little doubt of the continuing global influence of NGOs. As Salamon and Anheier (1996:129) conclude:

Fundamental historical forcesa widespread loss of confidence in the state, expanding communications, the emergence of a more vibrant commercial and professional middle class, and increased demands for a wide range of specialized serviceshave come together in recent years to expand the role of private, non-profit organizations in virtually every part of the world. Such organizations enjoy distinctive advantages in delivering human services, responding to citizen pressure, and giving expression to citizen demands. As a consequence, the nonprofit sector has come into its own as a major social and economic force, with substantial and growing employment and a significant share of the responsibility for responding to public needs.

Conclusion

The state emerged some seven to eight thousand years ago to politically integrate largely heterogeneous peoples and cultures. Military conquest was the main vehicle for their creation and maintenance. Two to three hundred years ago, the nation-state developed to fulfill

PART ONE / The Society of Perpetual Growth

a new need, that of economic integration. Military conquest as a device was not entirely abandoned, but new strategies of integration, such as improved means of communication and transportation, national education systems, and the ideology of nationalism, became preferred means of attaining desired economic ends.

The nation-state helped create the type of peoplelaborers and consumersre-quired to maintain and protect the interests of the capitalist. It created and maintained an unprecedented division of labor and imposed a shared culture that enabled workers to communicate with precision, while thirsting for the commodities that labor produced and which served as the basis of the elite's wealth.

More important, terror and violence remained state instruments of integration, serving to eliminate those who refused to assimilate into the new ideal of the nation-state or to mark as undesirable Others against whom the majority could unite. As a consequence, millions have died as victims of their own governments.

The need to integrate regions and territories economically, however, is being replaced by the need for global integration, while variations in the availability and price of labor is leading to massive labor migrations that threaten state boundaries. In the absence of a world government, organizations such as corporations and NGOs have moved in to fulfill functions once thought the purview of the state, as other organizations have developed to protect the rights of individuals and indigenous groupswho, as we shall see, have suffered disproportionately in the drive to create the nation-state.

With this discussion of the nation-state, we conclude our outline of the culture of capitalism and the origins of and relations among consumer, laborer, capitalist, and nation-state. These relationships may seem complex, but they are written on virtually every commodity we possess. For example, sneakers were once for kids or tennis or basketball players. Consumers for this commodity have been cleverly created through massive advertising campaigns involving, among other things, endorsements from popular sports figures, which not only make the shoes fashionable but allow Nike and other corporations to sell them for up to hundreds of dollars. To make the shoes Nike has, as they should do to please their investors, sought out cheap sources of labor. The labor for a pair of Nike sneakers costs less than $1 per pair, and the total amount Nike spends on labor is about the same as that paid to major sports figures for endorsements. As a consequence, Nike earns billions of dollars, returning much of it to banks and investors and using some to influence government legislation that would be favorable to its interests. To help generate this profit, nation-states support the entire operation by supporting and maintaining communication networks, financial institutions, and favorable labor legislation. Without the nation-state, businesses could not prosper, and consumers could not buy, at least not as cheaply as they do. Thus countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia offer tax breaks to Nike and control and discipline their labor force to ensure an inexpensive and docile work force, many of whom use their wages to purchase Nike products.

Thus while the historical, social, cultural, economic, political, and ideological factors that have helped create and maintain the culture of capitalism are in their totality complex, they can be identified in virtually every element of our culture, at least for those who care to look. Furthermore, as we shall see, these same factors contribute in one way or another to virtually every global issue that we discuss in the remainder of this book.

|

Politica de confidentialitate | Termeni si conditii de utilizare |

Vizualizari: 3751

Importanta: ![]()

Termeni si conditii de utilizare | Contact

© SCRIGROUP 2025 . All rights reserved