| CATEGORII DOCUMENTE |

| Bulgara | Ceha slovaca | Croata | Engleza | Estona | Finlandeza | Franceza |

| Germana | Italiana | Letona | Lituaniana | Maghiara | Olandeza | Poloneza |

| Sarba | Slovena | Spaniola | Suedeza | Turca | Ucraineana |

Esophagus and Gastroesophageal Junction Surgery

The Esophagus and Gastroesophageal procedures depicted here are excerpts from 'Mechanical Sutures In Operations On The Esophagus and Gastroesophageal Junction' by Felicien M. Steichen, M.D., F.A.C.S. and Ruth A. Wolsch, R.N., B.S. There are references to other figures and sections of this book. For further information on these references, please refer to: Cine-Med.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

This operation is indicated in patients with cancer of the proximal half of the thoracic esophagus, without metastatic extension below the diaphragm. The procedure shown here is a Beck-Jianu-Gavriliu reverse gastric tube.

The indications for routine, simultaneous, or delayed one-sided or bilateral neck dissection in the absence of macroscopically recognizable lymph node metastases remain unresolved. Studies, mostly by Japanese authors, give validity to the concept of radical neck dissection in operable and hopefully curable cancers of the cervical and thoracic esophagus. It would appear, however, that one-stage radical esophagectomy, creation of a substitute organ, and classic or modified neck dissection(s) represent a formidable challenge for these often nutritionally compromised patients, as well as for one team or even several teams of surgeons.

The concept of sentinel node mapping and biopsyso successfully used in operations for melanoma and breast cancermay help in solving this dilemma. For an elongated organ such as the esophagus, spanning three anatomical spacesthe neck, mediastinum, and abdomenand lacking the protective cover of a serosa, the lymphatic drainage can be unexpectedly erratic. Although the various patterns of drainage to the three potential lymph node basins are statistically well established for any tumor level, the knowledge that in a small number of patients all three locations are possible, could be interpreted as the need to radically excise all three lymphatic basins for any curative operative attemptan almost impossible task in an operation as demanding as is the excision and replacement of the esophagus. Therefore, the intraoperative detection, biopsy, and histological examination of sentinel nodes below the diaphragm and above the clavicles could be of great value in proving the absence or presence of metastatic disease. A clear upper abdominal lymphatic basin would establish the performance of a reverse gastric tube on a secure basis. Clear or only unilaterally involved cervical lymphatic basins would justify the withholding of radical neck dissections or establish the approach on the side of identified metastatic disease for both the lymph node dissection and the esophago-substitute anastomosis. Since the thoracic esophagus is always excisedeither by thoracotomy or thoracoscopya complete dissection of fatty and fibrous tissues in the posterior mediastinum, around the trachea, main bronchi, pericardium, and pulmonary vessels and aorta, on the side exposed by the approach, should be part of the excision, as far as the density of vital organs in this area allows an 'en bloc dissection.

The reverse gastric tube has a rich and dependable blood supply, requires only a slender channel to pass through in either substernal or posterior mediastinal position, and readily reaches the neck. The staple-constructed gastric tube transports food efficiently and empties readily into the stomach.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

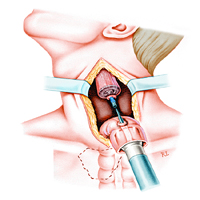

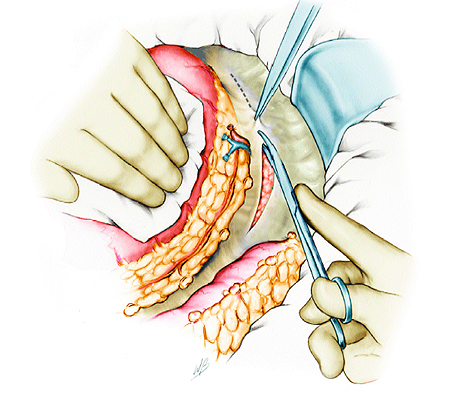

Step 1: Ligation and division of the short gastric vessels

The pertinent vascular anatomy is demonstrated. The gastroepiploic vessels are not always as beautifully continuous as they are shown, and, in fact, there usually is a gap high up on the fundus, bridged by reliable intramural vascular connections. While taking care to protect the left gastroepiploic arcade, the short gastric vessels are ligated and divided, either manually or with the LDS stapling instrument, close to their origin from the splenic vessels, following incision of and exposure through the gastrosplenic ligament. When activated, the LDS instrument places two crescent-shaped staples, ligating the tissue held within the jaw of the instrument, and evenly cuts between them.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

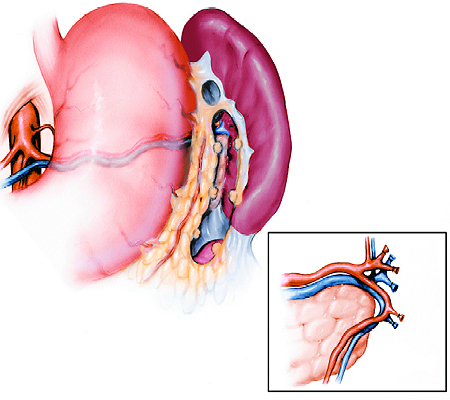

Step 2: Splenectomy if required

In the adult, splenectomy is usually required to facilitate the development of a tube long enough to reach the desired level at the cervical esophagus or hypopharynx. The tube is based on the left gastroepiploic vessels, originating from the splenic artery and vein. However, we make a reasonable effort (in line with the length of gastric tube required) to preserve the spleen and, in fact, succeed in doing this in children, in whom preservation of the spleen is an immunologic sine qua non.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

Step 3: Ligation and division of the gastrocolic omentum peripheral to the gastroepiploic vessels

The gastrocolic omentum is serially stapled and divided with the LDS instrument just peripheral to the gastroepiploic vessels. The right gastroepiploic vessels are divided at the level at which the tube is to be begun, peripheral to their origin from the gastroduodenal vessels.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

Step 4: Incision of the posterior peritoneum exposing the pancreas to provide mobility to the gastric tube

The stomach is lifted forward, and the loose posterior peritoneal attachments are divided, exposing the tail of the pancreas. The pancreas is elevated from its retroperitoneal bed, in a medial direction, to the level of the aorta. This, together with the Kocher maneuver for the duodenum, gives great mobility to the entire gastric tube.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

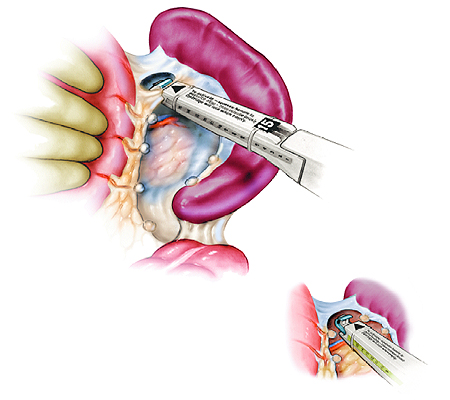

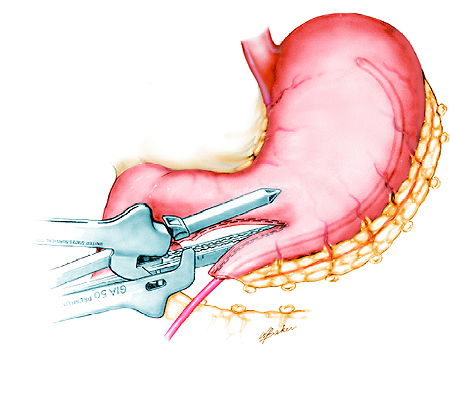

Step 5: Creation of the gastric tube

A French #38-40 bougie is inserted into the stomach through a distal incision in the greater curvature approximately 2 cm proximal to the pylorus. The stomach is serially stapled and divided longitudinally along the edge of the bougie with repeated applications of the GIA instrument.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

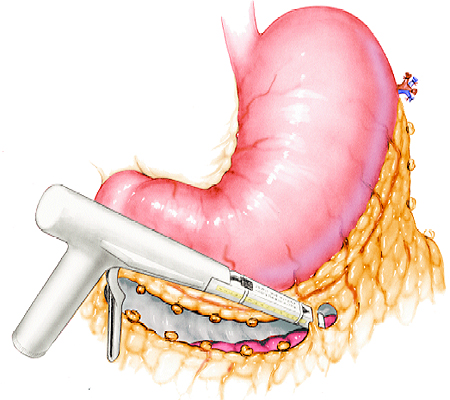

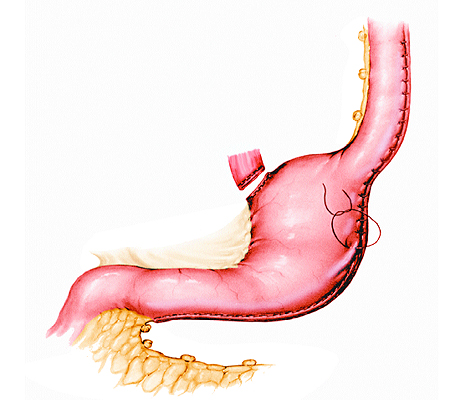

Step 6: Staple closure of the stomach and gastric tube oversewn

Several applications quickly produce a tube that will easily reach above the clavicles. We oversew the GIA staple closure of the stomach and tube with a continuous suture or, if time permits, interrupted sutures (as shown) for hemostasis of thick gastric walls. This also avoids overstretching the tube and creating gaps between individual staples as the tube is elevated into the neck or apex of the chest. Toward the upper end of the tube, a continuous oversewing suture is replaced by interrupted sutures so that it is not divided if the tube requires shortening, or is anastomosed to the cervical esophagus with the circular instrument. If esophagectomy is part of the operation, the esophagus is divided from the stomach with the GIA instrument. Early on in our experience with this procedure, we routinely added a pyloroplasty. However, it soon became evident that this was not a mandatory step and that the pylorus relaxed and emptied readily after a short postoperative period of hesitation.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

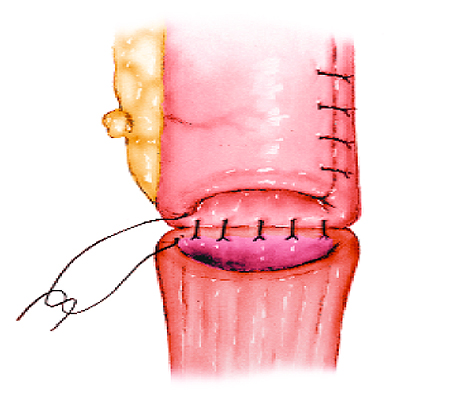

Step 7: End-to-end anastomosis of the cervical esophagus and the gastric tube

If the gastric tube is to be placed into the original bed in the posterior mediastinum, it is attached to the abdominal segment of the esophagus following liberation of the esophagus in the chest and neck. The esophageal specimen is then pulled out through the neck incision, and the gastric tube follows the upward movement without twists and undue resistance. Care is taken to maintain the blood supply on the left side of the gastric tube, which means that the long staple and suture line will gently rotate to the right side into the neck. The anastomosis of the tube to the hypopharyngeal and/or cervical esophageal stump can be achieved manually, in one layer, with full-thickness interrupted sutures as shown here, or with a posterior running suture and anterior interrupted sutures.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

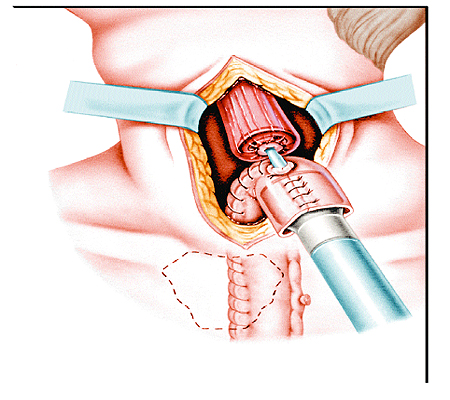

Step 8: End-to-side esophagogastrostomy

If the gastric tube is of sufficient length, a stapled circular anastomosis can be performed through the open end of the gastric tube as an end-to-side esophagogastrostomy, functioning essentially as an end-to-end anastomosis. The anvil of the EEA instrument is advanced into the esophageal stump, and the previously placed purse-string suture is tightened around the anvil shaft. With the gastric tube shaped like the handle of a cane, the instrument cartridge is positioned into the open gastric tube lumen and the center rod is advanced through the staple line, 5 to 6 cm beyond the open tube lumen. A manual purse-string suture is placed around the perforation site and tied around the center rod to ensure that the tissue is held securely within the EEA instrument. The anvil shaft and center rod are joined, the instrument is closed and activated, and a double stapling (circular through linear staple lines) anastomosis is performed.

Esophagectomy and Reverse Gastric Tube: Gavriliu I

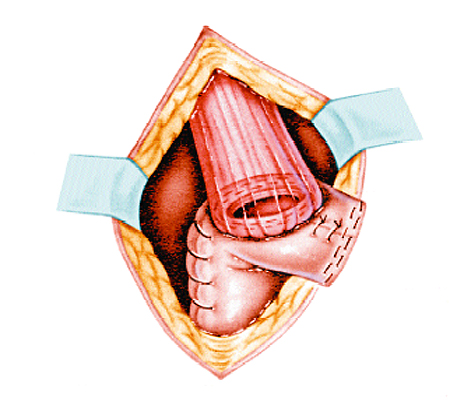

Step 9: Completed anastomosis

After removal of the EEA instrument and inspection for hemostasis, the gastric tube is closed with a linear stapler and the excess tissue is resected along the edge of the instrument.

This type of anastomosis, as well as the manual one, is unfortunately associated with a definite incidence of strictures because of the shape of the anastomosis and the long lateral closure of the gastric tube.

|

Politica de confidentialitate | Termeni si conditii de utilizare |

Vizualizari: 5558

Importanta: ![]()

Termeni si conditii de utilizare | Contact

© SCRIGROUP 2026 . All rights reserved