| CATEGORII DOCUMENTE |

| Bulgara | Ceha slovaca | Croata | Engleza | Estona | Finlandeza | Franceza |

| Germana | Italiana | Letona | Lituaniana | Maghiara | Olandeza | Poloneza |

| Sarba | Slovena | Spaniola | Suedeza | Turca | Ucraineana |

JAZZ

IN

THE U.S.A

Foreword

Music (and all art in general ) is an essential part of the human experience . Art hosts an invitation for the viewer or listener to invest a personal attentiveness . Unlike other mediums, the nature of music is tipped towards the emotional rather than intellectual. It is this personal connection with the music and all art that enables the patron to actually experience what is being communicated, rather than merely understanding the information .While all forms of music share this dynamic , Jazz, with its unique characteristics of collective improvisation ,exemplifies it.

The reason for which I have chosen to write about Jazz is my great love for music in general and jazz in particular. Secondly, the explanation resides in my strong belief that basic understanding and appreciation of music can only serve to broaden ones character and deepen the connection with those around us, because music is a universal language and such a rich and varied one indeed.

The history

of jazz music origins is attributed to the turn of the 20th century

My paper presents jazz from its early development until the present. Incorporating music from 19th and 20th century American popular music, jazz has, from its early 20th century inception, spawned a variety of subgenres, from New Orleans Dixieland dating from the early 1910s, big band-style swing from the 1930s and 1940s, bebop from the mid-1940s, a variety of Latin jazz fusions such as Afro-Cuban and Brazilian jazz from the 1950s and 1960s, jazz-rock fusion from the 1970s and late 1980s developments such as acid jazz, which blended jazz influences into funk and hip-hop. As the music has spread around the world it has drawn on local national and regional musical cultures, its aesthetics being adapted to its varied environments and giving rise to many distinctive styles.

Most genres of music involve the listener into the real, of the completed work as it was scored. Jazz draws the onlooker to a deeper league ,that of a partnership so to speak, of being along when each new phrase is created, with each inspired motive is often the interactive result of audience involvement. Jazz musics dynamic is its newness which can be attributed to the defining component-improvisation. A special chapter of my paper is dedicated to defining this special character of jaz.

The paper ends with the presentation of some big names in jazz. Among the biggest jazz players, it is hard not to mention: Louis Armstrong , Bessie Smith , Chet Baker , Billie Holiday , Duke Ellington , Coleman Hawkins , Lester Young , Ella Fitzgerald.

Table of contents

Foreword.2

What is jazz? .4

Origins.6

Types of jazz6

Miles Davis..13

Debates on jazz.17

Conclusion18

Bibliography..19

Jazz in the U.S.A

CHAPTER I

WHAT IS JAZZ?

Jazz is a primarily American musical art form which originated at the

beginning of the 20th century in African American communities in the

From its early development

until the present, jazz has also incorporated music from 19th and 20th century

American popular music. The word jazz began as a West Coast slang term

of uncertain derivation and was first used to refer to music in

Jazz has, from its early 20th century inception, spawned a variety of subgenres, from New Orleans Dixieland dating from the early 1910s, big band-style swing from the 1930s and 1940s, bebop from the mid-1940s, a variety of Latin jazz fusions such as Afro-Cuban and Brazilian jazz from the 1950s and 1960s, jazz-rock fusion from the 1970s and late 1980s developments such as acid jazz, which blended jazz influences into funk and hip-hop. As the music has spread around the world it has drawn on local national and regional musical cultures, its aesthetics being adapted to its varied environments and giving rise to many distinctive styles

The word jazz makes

one of its earliest appearances in

Jazz was introduced

to

One of the first known uses of the word jazz appears in a March 3, 1913, baseball article in the San Francisco Bulletin by E. T. Scoop Gleeson.

Definition

Jazz is hard to define because it spans from Ragtime waltzes to 2000s-era fusion. While many attempts have been made to define jazz from points of view outside jazz, such as using European music history or African music, jazz critic Joachim Berendt argues that all such attempts are unsatisfactory. One way to get around the definitional problems is to define the term jazz more broadly. Berendt defines jazz as a 'form of art music which originated in the United States through the confrontation of blacks with European music'; he argues that jazz differs from European music in that jazz has a 'special relationship to time, defined as 'swing'', 'a spontaneity and vitality of musical production in which improvisation plays a role'; and 'sonority and manner of phrasing which mirror the individuality of the performing jazz musician'.

Travis Jackson has also proposed a broader definition of jazz which is able to encompass all of the radically different eras: he states that it is music that includes qualities such as 'swinging', improvising, group interaction, developing an 'individual voice', and being 'open' to different musical possibilities'. Krin Gabbard claims that jazz is a construct or category that, while artificial, still is useful to designate a number of musics with enough in common to be understood as part of a coherent tradition.

While jazz may be difficult to define, improvisation is clearly one of its key elements. Early blues was commonly structured around a repetitive call-and-response pattern, a common element in the African American oral tradition. A form of folk music which rose in part from work songs and field hollers of rural Blacks, early blues was also highly improvisational. These features are fundamental to the nature of jazz. While in European classical music elements of interpretation, ornamentation and accompaniment are sometimes left to the performer's discretion, the performer's primary goal is to play a composition as it was written.

In jazz, however, the skilled performer will interpret a tune in very individual ways, never playing the same composition exactly the same way twice. Depending upon the performer's mood and personal experience, interactions with fellow musicians, or even members of the audience, a jazz musician/performer may alter melodies, harmonies or time signature at will. European classical music has been said to be a composer's medium. Jazz, however, is often characterized as the product of democratic creativity, interaction and collaboration, placing equal value on the contributions of composer and performer, 'adroitly weigh[ing] the respective claims of the composer and the improviser'.

In

Origins

Origins In the late 18th-century painting The

Old Plantation, African-Americans danced to banjo and percussion. By 1808

the Atlantic slave trade had brought almost half a million Africans to the

The blackface Virginia Minstrels in 1843, featuring

tambourine, fiddle, banjo and bones. In the early 19th century an increasing

number of black musicians learned to play European instruments, particularly

the violin, which they used to parody European dance music in their own

cakewalk dances. In turn, European-American minstrel show performers in blackface

popularized such music internationally, combining syncopation with European

harmonic accompaniment. Louis Moreau Gottschalk adapted African-American

cakewalk music, South American,

Represented by Scott Joplin in 1907.

The abolition of slavery led to new opportunities for education of freed African-Americans, but strict segregation meant limited employment opportunities. Black musicians provided 'low-class' entertainment at dances, in minstrel shows, and in vaudeville, and many marching bands formed. Black pianists played in bars, clubs and brothels, and ragtime developed.

Ragtime appeared as sheet music with the African- American entertainer Ernest Hogan's hit songs in 1895, and two years later Vess Ossman recorded a medley of these songs as a banjo solo 'Rag Time Medley'. Also in 1897, the white composer William H. Krell published his 'Mississippi Rag' as the first written piano instrumental ragtime piece. The classically-trained pianist Scott Joplin produced his 'Original Rags' in the following year, then in 1899 had an international hit with 'Maple Leaf Rag.' He wrote numerous popular rags, including, 'The Entertainer', combining syncopation, banjo figurations and sometimes call-and-response, which led to the ragtime idiom being taken up by classical composers including Claude Debussy and Igor Stravinsky. Blues music was published and popularized by W. C. Handy, whose 'Memphis Blues' of 1912 and 'St. Louis Blues' of 1914 both became jazz standards.

Represented by The Bolden Band around 1905.

The music of

Afro-Creole pianist Jelly Roll Morton

began his career in Storyville. From 1904, he toured with vaudeville shows

around southern cities, also playing in

The Original Dixieland Jass Band made the

first Jazz recordings early in 1917, their 'Livery Stable Blues'

became the earliest Jazz recording. That year numerous other bands made

recordings featuring 'jazz' in the title or band name, mostly ragtime

or novelty records rather than jazz. In September 1917 W.C. Handy's Orchestra of

Memphis recorded a cover version of 'Livery Stable Blues'. In

February 1918 James Reese Europe's 'Hellfighters' infantry band took

ragtime to

Prohibition

in the

Bix Beiderbecke formed The Wolverines in

1924. Also in 1924 Louis Armstrong joined the Fletcher Henderson dance band as

featured soloist for a year, then formed his virtuosic Hot Five band, also

popularising scat singing. Jelly Roll Morton recorded with the New Orleans

Rhythm Kings in an early mixed-race collaboration, then in 1926 formed his Red

Hot Peppers. There was a larger market for jazzy dance music played by white

orchestras, such as Jean Goldkette's orchestra and Paul Whiteman's orchestra.

In 1924 Whiteman commissioned Gershwin's Rhapsody in Blue, which was

premièred by Whiteman's Orchestra. Other influential large ensembles

included Fletcher Henderson's band, Duke Ellington's band (which opened an

influential residency at the Cotton Club in 1927) in

The 1930s belonged to popular swing big bands, in which some virtuoso soloists became as famous as the band leaders. Key figures in developing the 'big' jazz band included bandleaders and arrangers Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey, Duke Ellington, Benny Goodman, Fletcher Henderson, Earl Hines, Glenn Miller, and Artie Shaw.Trumpeter, bandleader and singer Louis Armstrong was a much-imitated innovator of early jazz.

Swing was also dance music and it was

broadcast on the radio 'live' coast-to-coast nightly across

Over time, social strictures regarding racial segregation began to relax, and white bandleaders began to recruit black musicians. In the mid-1930s, Benny Goodman hired pianist Teddy Wilson, vibraphonist Lionel Hampton, and guitarist Charlie Christian to join small groups. An early 1940s style known as 'jumping the blues' or jump blues used small combos, up-tempo music, and blues chord progressions. Jump blues drew on boogie-woogie from the 1930s. Kansas City Jazz in the 1930s marked the transition from big bands to the bebop influence of the 1940s.

In the late 1930s

there was a revival of 'Dixieland' music, harkening back to the

original contrapuntal

Bebop

Bebop In the early 1940s bebop performers helped to shift jazz from danceable popular music towards a more challenging 'musician's music.' Differing greatly from swing, early bebop divorced itself from dance music, establishing itself more as an art form but lessening its potential popular and commercial value. Since bebop was meant to be listened to, not danced to, it used faster tempos. Beboppers introduced new forms of chromaticism and dissonance into jazz; the dissonant tritone (or 'flatted fifth') interval became the 'most important interval of bebop'and players engaged in a more abstracted form of chord-based improvisation which used 'passing' chords, substitute chords, and altered chords. The style of drumming shifted as well to a more elusive and explosive style, in which the ride cymbal was used to keep time, while the snare and bass drum were used for unpredictable, explosive accents.

These divergences from the jazz mainstream of the time initially met with a divided, sometimes hostile response among fans and fellow musicians, especially established swing players, who bristled at the new harmonic sounds. To hostile critics, bebop seemed to be filled with 'racing, nervous phrases'Despite the initial friction, by the 1950s bebop had become an accepted part of the jazz vocabulary. The most influential bebop musicians included saxophonist Charlie Parker, pianists Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk, trumpeters Dizzy Gillespie and Clifford Brown, tenor sax player Lester Young, and drummer Max Roach. (See also List of bebop musicians).

By the end of the 1940s, the nervous

energy and tension of bebop was replaced with a tendency towards calm and

smoothness, with the sounds of cool jazz, which favoured long, linear melodic

lines. It emerged in

Hard bop is an extension of bebop (or 'bop') music that incorporates influences from rhythm and blues, gospel music, and blues, especially in the saxophone and piano playing. Hard bop was developed in the mid-1950s, partly in response to the vogue for cool jazz in the early 1950s. The hard bop style coalesced in 1953 and 1954, paralleling the rise of rhythm and blues. Miles Davis' performance of 'Walkin'' the title track of his album of the same year, at the very first Newport Jazz Festival in 1954, announced the style to the jazz world. The quintet Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, fronted by Blakey and featuring pianist Horace Silver and trumpeter Clifford Brown, were leaders in the hard bop movement along with Davis. (See also List of Hard bop musicians)

Modal jazz

Modal jazz Modal jazz is a development beginning in the later 1950s which takes the mode, or musical scale, as the basis of musical structure and improvisation. Previously, the goal of the soloist was to play a solo that fit into a given chord progression. However, with modal jazz, the soloist creates a melody using one or a small number of modes. The emphasis in this approach shifts from harmony to melody. Miles Davis recorded one of the best selling jazz albums of all time in the modal framework: Kind of Blue, an exploration of the possibilities of modal jazz. Other innovators in this style include John Coltrane and Herbie Hancock.

Free jazz and the related form of

avant-garde jazz broke through into an open space of 'free tonality'

in which meter, beat, and formal symmetry all disappeared, and a range of World

music from

Soul jazz was a development of hard

bop which incorporated strong influences from blues, gospel and rhythm and

blues in music for small groups, often the organ trio which partnered a

Soul jazz was a development of hard

bop which incorporated strong influences from blues, gospel and rhythm and

blues in music for small groups, often the organ trio which partnered a

In the late 1960s and early 1970s the hybrid form of jazz-rock fusion was developed by combining jazz improvisation with rock rhythms, electric instruments, and the highly amplified stage sound of rock musicians such as Jimi Hendrix. Miles Davis made the breakthrough into fusion in 1970s with his album Bitches Brew, and by 1971, two influential fusion groups formed: Weather Report and the Mahavishnu Orchestra. Although jazz purists protested the blend of jazz and rock, some of jazz's significant innovators crossed over from the contemporary hard bop scene into fusion. Jazz fusion music often uses mixed meters, odd time signatures, syncopation, and complex chords and harmonies. In addition to using the electric instruments of rock, such as the electric guitar, electric bass, electric piano, and synthesizer keyboards, fusion also used the powerful amplification, 'fuzz' pedals, wah-wah pedals, and other effects used by 1970s-era rock bands. Notable performers of jazz fusion included Miles Davis, keyboardists Joe Zawinul, Chick Corea, Hiromi Uehara, Herbie Hancock, vibraphonist Gary Burton, drummer Tony Williams, guitarists Larry Coryell and John McLaughlin, Frank Zappa, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, and bassists Jaco Pastorius and Stanley Clarke.

There was a resurgence of interest in

jazz and other forms of African American cultural expression during the Black

Arts Movement and Black nationalist period of the early 1970s. Musicians such

as Pharoah Sanders, Hubert Laws and Wayne Shorter began using African

instruments such as kalimbas, cowbells, beaded gourds and other instruments not

traditional to jazz. Musicians began improvising jazz tunes on unusual

instruments, such as the jazz harp (Alice Coltrane), electrically-amplified and

wah-wah pedaled jazz violin (Jean-Luc Ponty), and even bagpipes (Rufus Harley).

Jazz continued to expand and change, influenced by other types of music, such

as world music, avant garde classical music, and rock and pop music. Guitarist John

McLaughlin's Mahavishnu Orchestra played a mix of rock and jazz infused with East

Indian influences. The ECM record label began in

Jazz in

the 1980s2000s

Jazz in

the 1980s2000s In the 1980s, the jazz community shrank dramatically and split. A mainly older audience retained an interest in traditional and 'straight-ahead' jazz styles. Wynton Marsalis strove to create music within what he believed was the tradition, creating extensions of small and large forms initially pioneered by such artists as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington. In 1987, the US House of Representatives and Senate passed a bill proposed by Democratic Representative John Conyers, Jr. to define jazz as a unique form of American music stating, among other things, 'that jazz is hereby designated as a rare and valuable national American treasure to which we should devote our attention, support and resources to make certain it is preserved, understood and promulgated.'

In the early 1980s, a lighter commercial

form of jazz fusion called pop fusion or 'smooth jazz' became

successful and garnered significant radio airplay. Smooth jazz saxophonists

include Grover Washington, Jr., Kenny G and Najee. Smooth jazz received frequent

airplay with more straight-ahead jazz in quiet storm time slots at radio

stations in urban markets across the

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, several subgenres fused jazz with popular music, such as Acid jazz, nu jazz, and jazz rap. Acid jazz and nu jazz combined elements of jazz and modern forms of electronic dance music. While nu jazz is influenced by jazz harmony and melodies, there are usually no improvisational aspects. Jazz rap fused jazz and hip-hop. Gang Starr recorded 'Words I Manifest,' 'Jazz Music,' and 'Jazz Thing', sampling Charlie Parker and Ramsey Lewis, and collaborating with Branford Marsalis and Terence Blanchard. Beginning in 1993, rapper Guru's Jazzmatazz series used jazz musicians during the studio recordings.

In the 2000s, straight-ahead jazz

continues to appeal to a core of listeners. Well-established jazz musicians

whose careers span decades, such as Dave Brubeck, Wynton Marsalis, Sonny

Rollins, and Wayne Shorter continue to perform and record. In the 1990s and

2000s, a number of young musicians emerged including US pianists Brad Mehldau, Jason

Moran, and Vijay Iyer, guitarist Kurt Rosenwinkel, vibraphonist Stefon Harris,

trumpeters Roy Hargrove and Terence Blanchard, and saxophonists Chris Potter

and Joshua Redman. The more experimental end of the spectrum has included

Norwegian pianist Bugge Wesseltoft, the internationally popular Swedish trio E.S.T.

and

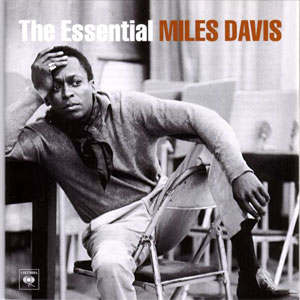

CHAPTER III

MILES DAVIS

Miles Dewey

Davis III

(May 25, 1926 September 28, 1991) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader,

and composer.

Miles Dewey

Davis III

(May 25, 1926 September 28, 1991) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader,

and composer.

Widely considered one of the most

influential musicians of the 20th century, Davis was at the forefront of almost

every major development in jazz from World War II to the 1990s: he played on

various early bebop records and recorded one of the first cool jazz records; he

was partially responsible for the development of hard bop and modal jazz, and

both jazz-funk and jazz fusion arose from his work with other musicians in the

late 1960s and early 1970s; and his final album blended jazz and rap. Many

leading jazz musicians made their names in

As

a trumpeter,

On March 13, 2006

Early

life (1926 to 1944)

Early

life (1926 to 1944) Miles was born on May 25, 1926 to a relatively

affluent family in

By the age of 16,

In 1944, the Billy Eckstine band visited

In 1944, the Billy Eckstine band visited

That fall, following graduation from

high school, Miles moved to

In the mid to late 1940s, Miles played in many bebop combos, most notably with Charlie Parker's Quintet. In 1948 he started organizing musicians together for a whole new style of jazz music. The sessions they recorded in 1949 and 1950 were later retitled Birth of the Cool. The music was meant to be more laid back and mellow than the fast rhythms and elaborate solos associated with regular bebop music. These recordings inspired a whole new movement in jazz music, typically referred to as cool jazz. After recording more in both the bebop and cool genres, Miles made Walkin', a seminal record that many would come to mark as the birth of the hard bop genre. Like cool jazz, the music was slower than regular bebop, but unlike cool jazz, it had a much harder, grooving beat to it. It took in certain elements of rhythm & blues, and inspired a whole host of new music in the decade to come.

First great quintet and

sextet (1955 to 1958)

First great quintet and

sextet (1955 to 1958) In 1955,

The quintet was never stable, however;

several of the other members used heroin, and the Miles Davis Quintet disbanded

in early 1957. That year,

After recording Milestones,

In March and April 1959,

The same year, while taking a break

outside the famous Birdland nightclub in

The same year, while taking a break

outside the famous Birdland nightclub in

In 1963,

The rhythm section clicked very quickly

with each other and the horns; the group's rapid evolution can be traced

through the aforementioned studio album, In

Coleman left in the spring of 1964, to

be replaced by avant-garde saxophonist Sam Rivers, on the suggestion of Tony

Williams. Rivers remained in the group only briefly, but was recorded live with

the quintet in

By the end of the summer,

Grammy Award for Best Jazz

Instrumental Performance, Soloist for We Want Miles (1982)

Grammy Award for Best Jazz

Instrumental Performance, Soloist for We Want Miles (1982)

CHAPTER IV

There have been debates in the jazz community over the definition and the boundaries of jazz. Although alteration or transformation of jazz by new influences has often been initially criticized as a debasement, Andrew Gilbert argues that jazz has the ability to absorb and transform influences from diverse musical styles.While some enthusiasts of certain types of jazz have argued for narrower definitions which exclude many other types of music also commonly known as 'jazz', jazz musicians themselves are often reluctant to define the music they play. Duke Ellington summed it up by saying, 'It's all music.' Some critics have even stated that Ellington's music was not jazz because it was arranged and orchestrated. On the other hand Ellington's friend Earl Hines's twenty solo 'transformative versions' of Ellington compositions (on Earl Hines Plays Duke Ellington recorded in the 1970s) were described by Ben Ratliff, the New York Times jazz critic, as 'as good an example of the jazz process as anything out there.'

Commercially-oriented or popular

music-influenced forms of jazz have both long been criticized, at least since

the emergence of Bop. Traditional jazz enthusiasts have dismissed Bop, the

1970s jazz fusion era (and much else) as a period of commercial debasement of

the music. According to Bruce Johnson, jazz music has always had a

'tension between jazz as a commercial music and an art form'. Gilbert

notes that as the notion of a canon of jazz is developing, the achievements of

the past may be become 'privileged over the idiosyncratic creativity

and innovation of current artists. Village Voice jazz critic Gary Giddins

argues that as the creation and dissemination of jazz is becoming increasingly

institutionalized and dominated by major entertainment firms, jazz is facing a

'perilous future of respectability and disinterested acceptance.'

David Ake warns that the creation of norms in jazz and the establishment of a

jazz tradition may exclude or sideline other newer, avant-garde forms of

jazz. Controversy has also arisen over new forms of contemporary jazz created

outside the

Conclusion

Jazz is a primarily American musical art form which originated at the

beginning of the 20th century in African American communities in the

The word jazz makes one of its earliest appearances in San Francisco baseball writing in 1913,and is often defined as music that includes qualities such as 'swinging', improvising, group interaction, developing an 'individual voice', and being 'open' to different musical possibilities'. Krin Gabbard claims that jazz is a construct or category that, while artificial, still is useful to designate a number of musics with enough in common to be understood as part of a coherent tradition

Jazz is among

Jazz is not the result of choosing a tune, but an ideal that is created first in the mind, inspired by ones passion, and willed next in playing music. Its unique expression draws from life experience and human emotion as the inspiration of the creative force and through this discourse is chronicled the history of a people.

I would like to end with two quotes that add further dimension to the meaning of jazz:

The real power of Jazz is that a group of people can come together and createimprovised art and negotiate their agendasand that negotiation is the art ( Wynton Marsalis )

Jazz means incredible freedom. But the more you learn about it, the more tools you have to make that freedom really count in different ways. (Miles Davis)

Bibliography

|

Politica de confidentialitate | Termeni si conditii de utilizare |

Vizualizari: 2173

Importanta: ![]()

Termeni si conditii de utilizare | Contact

© SCRIGROUP 2025 . All rights reserved